Imagine you lived in a world where your best friend could turn you in for saying the wrong thing, where your own child could rise against you in the name of politics. Imagine a world where sitting down to eat dinner was not safe from government control.

This isn’t a figment of my imagination, nor is it a scene from a novel. It was real life, and it defined an entire generation of Mao Zedong’s China.

From the late 1950s through to the 1970s, Mao Zedong launched bold campaigns that promised to turn China into a powerful nation. However, with these promises, speeches, and slogans came suffering; people who lived normal lives paid the price.

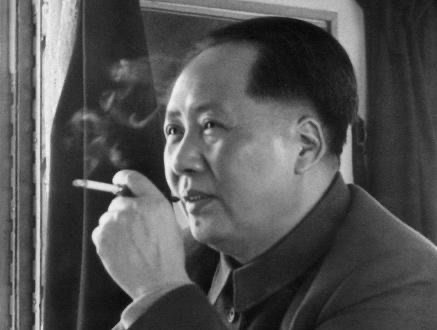

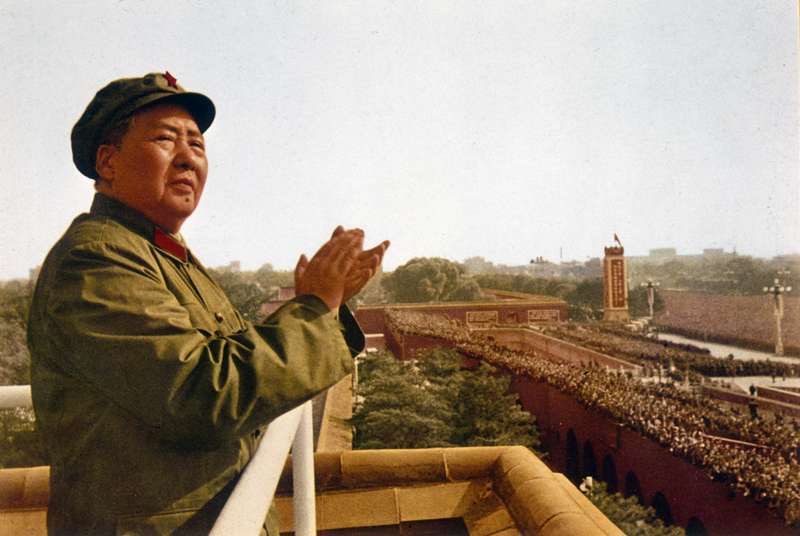

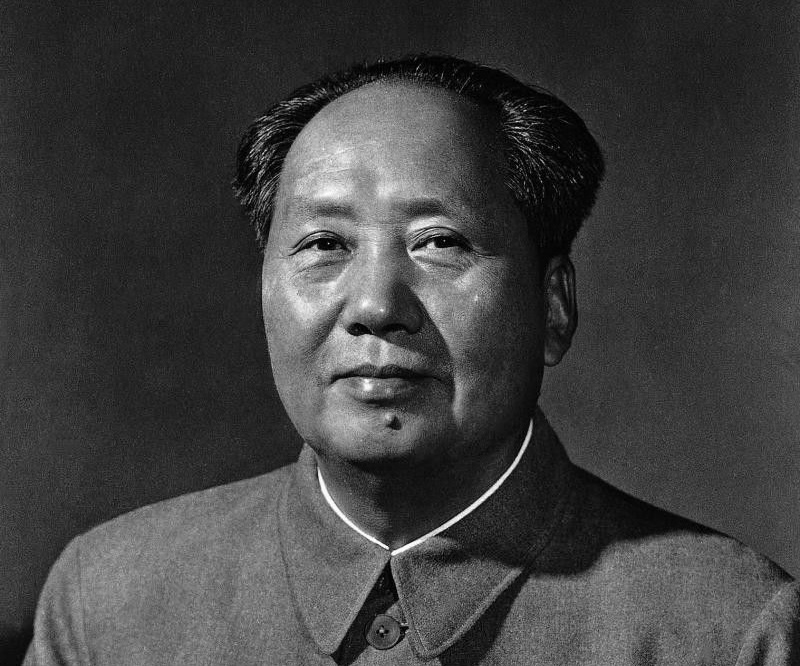

When people think of Mao Zedong, they often imagine the serious-looking face on posters, crowds of people in Tiananmen Square waving at posters, or that little red book that seemed to follow every citizen around like a national ID card.

His campaigns shaped what families ate or didn’t eat, how children treated their parents, and even neighbors’ trust in each other.

However, Mao was not just a leader in history textbooks. He was a leader whose policies disrupted people’s lives and changed the norm.

From the Great Leap Forward to the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s campaigns were more than just political experiments; they were experiences that people passed through. His campaigns shaped what families ate or didn’t eat, how children treated their parents, and even whether neighbors could trust each other.

Kitchens turned into collective messy halls, starvation spread through villages, teachers were attacked by their students, and families broke apart as fear and loyalty to Mao constantly clashed under the same roof. Life in mid-20th-century China became a battleground of ideology, fear, and survival, with far-reaching consequences.

This is not just a story about politics; it is about how one man’s vision profoundly affected the smallest details of people’s daily lives and left scars that are still visible today.

Let’s travel back in time and walk through the China of Mao Zedong. Not the dusty government reports, but through the eyes of the people who were trying to live during his reign.

The Visionary and the Village: Mao Zedong’s Dream for China

Mao Zedong rose to power after leading the communist party to victory in 1949. For many people, his triumph meant the end of war, chaos, and foreign domination. The people had great hope in Mao, especially given his promises of a new China —a strong and independent nation free from poverty.

Mao’s vision was not just about politics. He wanted to change how people lived, including their daily activities. He believed China’s strength would not come from slow progress, but from massive campaigns that shook people out of their old ways of thinking. For Mao, the society had to be reshaped, including families, schools, farms, factories, and even friendships.

This is where the story begins: the tale of promises that quickly became very personal.

The Great Leap Forward: When Dinner Disappeared

In 1958, Mao launched his most ambitious experiment: The Great Leap Forward. On paper, the whole plan sounded inspiring. China would leap from a poor, agrarian society to a modern, industrial power almost overnight. Farmers would become steel producers, and villages would be transformed into giant collective farms known as communes.

Mothers no longer cooked for their children; instead, everyone lined up for food in messy halls.

However, for ordinary people, the Great Leap Forward did not feel like progress at all. It felt more like losing control over daily life and activities.

Families Lost Their Kitchens

Communal canteens replaced home cooking. Mothers no longer cooked for their children; instead, everyone lined up for food in messy halls. At first, there was excitement. Who wouldn’t be happy to get free meals, which include an endless supply of rice and meat stews? So yes, they were excited about it at first. However, as harvests failed, meals that were once hearty turned into watery gruel.

Work Swallowed Life

Men and women were sent to the fields from dawn to dusk, while children joined in “production teams.” Even household chores became collective. Imagine being told that your backyard, your tools, and your animals now belonged to the commune.

Steel Over Survival

Mao pushed villages to build “backyard furnaces” to smelt steel. Every single household had to do this. Families melted at their pots, pans, and even farm tools in order to meet the quotas. You would think this would result in industrial progress; well, it did not. It only resulted in piles of useless, brittle metal.

Parents skipped meals so their children could eat, and neighbors fought over scraps. Some people even resorted to desperate measures just to survive.

The consequences of Mao’s plan were devastating. Poor planning, inflated crop yield reports, and forced grain exports left the countryside barren. By the early 1960s, famine swept across China. Historians estimate the death toll to be around 30 to 45 million during his reign. It was one of the deadliest famines in human history.

Parents skipped meals so their children could eat, and neighbors fought over scraps. Some people even resorted to desperate measures just to survive. For many families who lived in that era, it wasn’t just about hunger. It was also about watching trust slip away. The Great Leap Forward did not just starve stomachs; it starved relationships by breaking down the bonds of trust that held villages together.

The Cultural Revolution: When Children Became Rebels

If the Great Leap Forward reshaped farms and kitchens, the Cultural Revolution that occurred between 1966 and 1976 stormed into classrooms, neighbourhoods, and even bedrooms. Mao launched this revolution to “purify” China from old ideas, traditions, and the things he called enemies of socialism. However, in practice, it turned the society upside down.

Imagine sitting in class one day, and the next thing you know, you are watching your teacher being dragged outside and humiliated.

The most striking symbol of this chaos was the Red Guards. Millions of students, including teenagers and even middle-schoolers, were encouraged to rise up against “counter-revolutionaries.” They were all armed with Mao’s Little Red Book, allowing them to easily target teachers, intellectuals, and sometimes even their own parents.

Their daily life turned into an unpredictable stage of loyalty tests. In schools, students denounced their teachers, lessons shifted from math or literature to sessions where they chanted slogans and memorized Mao’s words. Imagine sitting in class one day, and the next thing you know, you are watching your teacher being dragged outside and humiliated.

In neighborhoods, neighbors spied on each other. If a neighbor hangs a family photo of Confucius, plays old music, or even speaks a dialect other than Mandarin, it could get them branded as “backward.”

At home, families were torn apart. Some children reported their parents for criticizing Mao. Fathers and mothers, who were once protectors, became potential “class enemies.“

Fear was a constant. Was your bookshelf too full of “bourgeois” literature? Was your dressing too “westernized?” Could your family’s past — being a landlord, a merchant, or even just better off than others — come back to haunt you?

The Cultural Revolution was not only about politics; it was about identity. People had to erase parts of themselves, their traditions, their language, and their family history just to survive.

The Personal Cost of Collectivization

One of Mao’s most transformative policies was collectivization. Families who had worked on small plots of land for generations suddenly found themselves farming collectively. For many people, this meant:

- Losing ownership of tools, animals, and crops.

- Being assigned to jobs instead of choosing them.

- Working long hours for “work points” rather than wages.

It was not just an economic change, it was also emotional. Land was more than soil to these people; it was memory, identity, and legacy. Families who once celebrated harvests together now shared bland meals in communal halls. The joy of growing food for your own children vanished into state quotas.

This shift blurred family life. Parents worked until they were exhausted, children were often raised in communal nurseries. Traditional rhythms like family dinners, seasonal rituals, and ancestral worship all faded.

Collectivization was not just about farming; it was about shaping how families functioned.

Mao’s Ideology in the Living Room

What made Mao’s campaigns distinct from traditional government policies was their profound impact on private life. His ideology was not confined to speeches. It entered homes through propaganda, posters, loudspeakers, and the Little Red Book.

Posters screamed slogans like “Serve the People” or “Smash the Four Olds!” They were not just decorations, they were daily reminders of the presence of the state. Loudspeakers in villages blasted political messages each morning. It was like an alarm clock that was set by the government.

The Little Red Book became both a symbol of loyalty and a survival tool. Forgetting a single quote or refusing to carry it could make you look suspicious.

Imagine your living room, a private space that used to be full of warmth, now covered in portraits of Mao Zedong. A space for relaxing, becomes a place where even conversations have to be filtered because one wrong word could mean disaster.

The Ripple Effects: What Mao Left Behind

By the time Mao died in 1976, China was deeply scarred. His policies left deep consequences that shaped not only the 20th century but also modern China, some of which include;

- Population Loss and Trauma: The famine that was caused by the Great Leap Forward devastated entire generations. Families carried the grief and silence of those years into the future.

- Distrust in Communities: Mao’s Cultural Revolution taught people to fear neighbors, colleagues, and even relatives. This culture of suspicion lingered long after Mao died.

Some people praise him for unifying the country and giving it global stature, others mourn the suffering that was caused by his experiments.

- Disrupted Education: An entire decade of schools focused on ideology instead of learning, which caused many of those who grew up during the Cultural Revolution to miss out on crucial education.

- Cultural Loss: Ancient temples, books, and traditions were destroyed. Although some of them were later rebuilt, much of China’s heritage was irreparably damaged.

- Reshaped Politics: The combination of Mao’s charisma and control set a template for how the Communist Party could continue to govern, with both mass campaigns and strict censorship.

Yet, despite the pain, Mao was still remembered with complexity in China. Some people praise him for unifying the country and giving it global stature, while others mourn the suffering that was caused by his experiments

We still revisit Mao’s mid-century campaigns today because of their lasting effects and the consequences that continue to impact China. We can still see the emphasis on collective loyalty over individuality in how the state manages society today. The memory of famine and upheaval shaped how China handles food security and political dissent, and we also can’t forget the scars of lost traditions.

Most importantly, Mao Zedong’s campaigns remind us of how powerful and dangerous political visions can be when they invade the essence of everyday life.

Final Thoughts: When Ideology Became Intimate

From the Great Leap Forward to the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong’s policies were not distant experiments. They lived in people’s kitchens, schools, and family gatherings. They determined whether you ate dinner, whether you trusted your neighbor, whether you could honor your ancestors, or even whether your child might betray you in the name of revolution.

Life in mid-century China was not just shaped by ideology; it was consumed by it. While decades have passed, the consequences, including hunger, trauma, lost traditions, and political caution, still resonate through Chinese society today.

This is why remembering Mao’s campaigns is so important, not as dusty history, but as living lessons about the fragile line between hope and horror.

Wild, isn’t it? A kitchen, a classroom, even family dinners, all turned into battlefields of just one man’s ideology. If you had lived in Mao’s China, which part of daily life do you think would have been the hardest for you to give up? Comment below and share. We would love to hear your take.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Mao Zedong biography (overview) → Encyclopaedia Britannica: “Mao Zedong”

- Mao Zedong historic figure summary → BBC History: “Mao Zedong”

- Mao’s rise to power → Encyclopaedia Britannica: “Mao Zedong – The road to power”

- Who was Mao Zedong? → ChinaFile/NYRB China Archive: “Who Was Mao Zedong?”

- Cultural Revolution & Red Guards (1966–1976 daily life, students turning on teachers, family betrayal → History.com (2023: “Cultural Revolution”)