A bomb blast interrupted normal life in Nsukka, a vibrant town in South-Eastern Nigeria. It was July 6, 1967, the first day of the deadly Nigerian Civil War that would shake the foundations of the young West-African nation.

Before then, life went on as usual. Stalls in one of the village’s markets were packed with fruits, vegetables, livestock, and foodstuffs. Buyers and sellers exchanged words until they reached a mutually acceptable price. Wads of cash moved from hand to hand.

It was a regular Thursday in the market, except that a week before, on May 30, 1967, the South-Eastern region of Nigeria had declared independence. They were now the Republic of Biafra.

So, rumors were flying around. Would the Nigerian forces attack, or would they explore more peaceful means to resolve the issue? No one was sure until a deafening sound rang across the market.

After a few seconds of silence and confusion, horrifying cries rang out across the market. Men and women screamed in pain as they struggled to free themselves from the rubble of furniture, sand, and crushed foodstuffs.

…One of Africa’s bloodiest conflicts. A war fueled by ego, ethnic division, and oil.

The ground was red. Blood flowed freely from injured and dead victims.

A Nigerian military plane had just dropped a bomb on the market. The Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Biafran War, had begun.

Here, we’d take a look at what led to one of Africa’s bloodiest conflicts. A war fueled by ego, ethnic division, and oil.

It is a sad story of massacres, starvation, and colonial influence. One that shaped Nigeria’s destiny, altered its political scene to date, and tested global humanitarian response.

Nigeria’s Fragile Beginnings

To fully understand how Nigeria got to that point, we must examine the events that followed its birth. After decades of agitation, the British finally granted Nigeria independence on October 1, 1960. It was a joyous moment for the most populous black nation.

The future seemed incredibly bright. Blessed with natural resources such as crude oil and gas, rich soil, and large rivers, it had all it needed to make it to the top. Already, it was the envy of the whole continent of Africa.

However, there was one challenge on its way to prosperity. Nigeria was composed of numerous ethnic groups that hadn’t fully integrated.

The British had forced everyone together. But three ethnic zones stood out. These are the predominantly Hausa-Fulani North, the mostly Christian Yoruba South West, and the majorly Christian Igbo South East.

Regional governments ran each of these zones. But they were supervised by a prime minister. The smaller tribes hid under the umbrella of the three bigger ones.

Things Began to Fall Apart

Suddenly, in January 1966, a military coup occurred—a bloody one at that. Most of the rebellious soldiers were from the Igbo-dominated South East. At the same time, most of the fatalities were from the North.

The fragile cords of unity began to break.

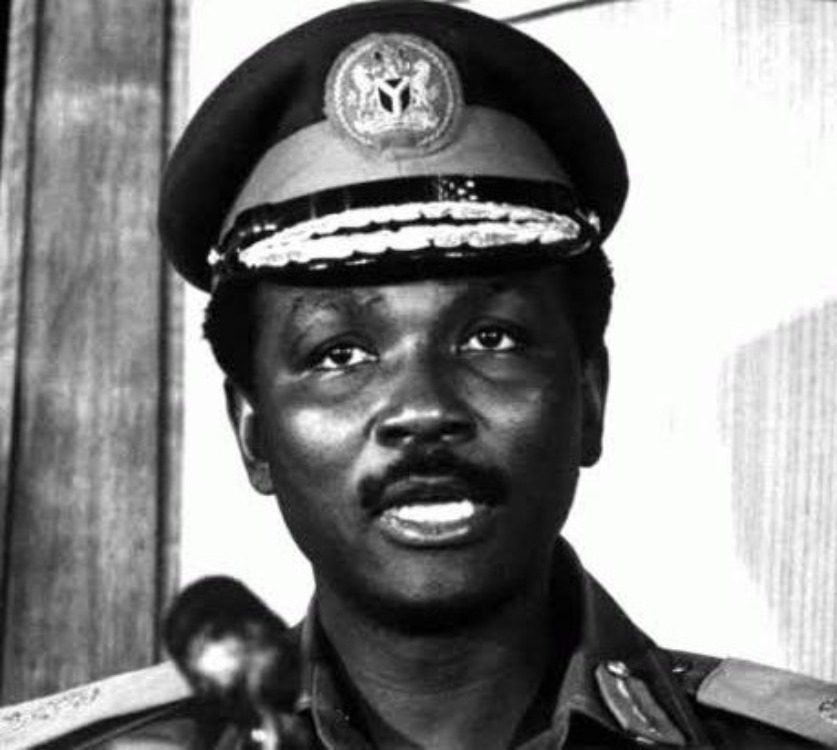

A new military leader emerged after the coup. Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi fought and defeated the coup plotters, stepping in as the first-ever military ruler or Head of State.

He was from the Igbo-speaking South East, the same ethnicity as most of the coup agents. This was a huge issue. To worsen matters, he failed to address the coup planners adequately.

Deadly riots broke out in the North, leading to the deaths of thousands of Igbos.

This raised suspicion among the other two major groups, especially the Hausa-Fulani. His leniency towards the issue portrayed a level of sympathy for the rebels. As a result, soldiers from the other two major zones didn’t trust their new leader.

Six months after the first coup, soldiers from the North and Southwest staged another coup, removing him. They then installed a soldier from the North, General Yakubu Gowon, as the new Head of State.

In addition, deadly riots broke out in the North, leading to the deaths of thousands of Igbos. The regional head of the South East, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, condemned the killings.

He called on Gen. Gowon to arrest the killers. But little or nothing was done. This was the spark that led to the Biafran secession in 1967.

The Birth of Biafra

On May 30, 1967, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, the military governor of the Eastern Region, declared the independence of the Republic of Biafra.

His people were solidly behind him. The Igbos felt that Nigeria no longer wanted them. Biafra represented an escape from persecution. It was freedom from an unwanted alliance and the beginning of a new dawn.

Colonel Ojukwu unveiled a new flag and introduced a new currency. The country’s new logo was a yellow rising sun. But for the Nigerian government, the Biafran secession was unacceptable.

Aside from the issue of unity, there was another stake at play: oil.

Of course, the British sided with the Nigerian government. Any disruption of the Nigerian project would harm the oil interests of the former colonial masters.

Biafra contained most of the nation’s oil reserves. To lose the territory was to plunge into economic collapse. Oil sale was the primary source of Nigeria’s wealth.

Within a few weeks, war broke out.

Of course, the British sided with the Nigerian government. Any disruption of the Nigerian project would harm the oil interests of the former colonial masters.

Two British companies, Shell and British Petroleum, were the major drillers of Nigerian oil. The British weren’t ready to lose their grip on the South East. The region was the hen that laid the golden eggs.

The Soviet Union also supported the federal government. They supplied arms. But France, Britain’s colonial arch-rival, supported the breakaway region.

Blockade and Starvation

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the Biafran War was the weaponisation of starvation. At one point, the Nigerian forces began to block the supply of aid to Biafra.

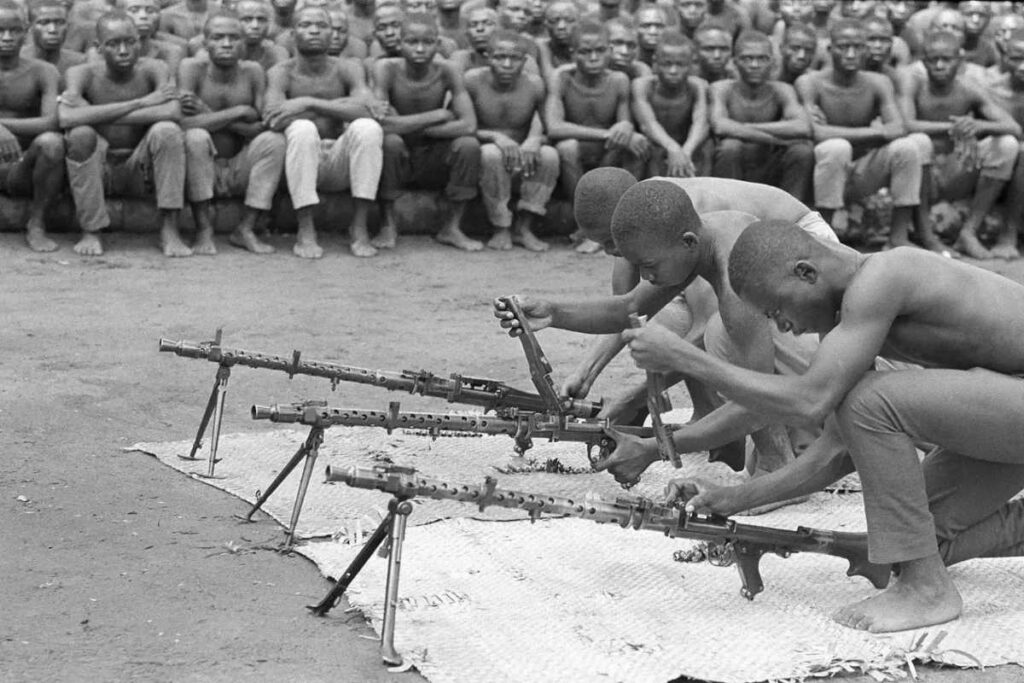

Federal forces blocked off the region by land, air, and sea. Biafra was denied food, medicine, and supplies. Air raids such as the one at Nsukka destroyed markets and foodstuffs. Farmers were scared to till the soil, and bombs destroyed the little farmlands remaining.

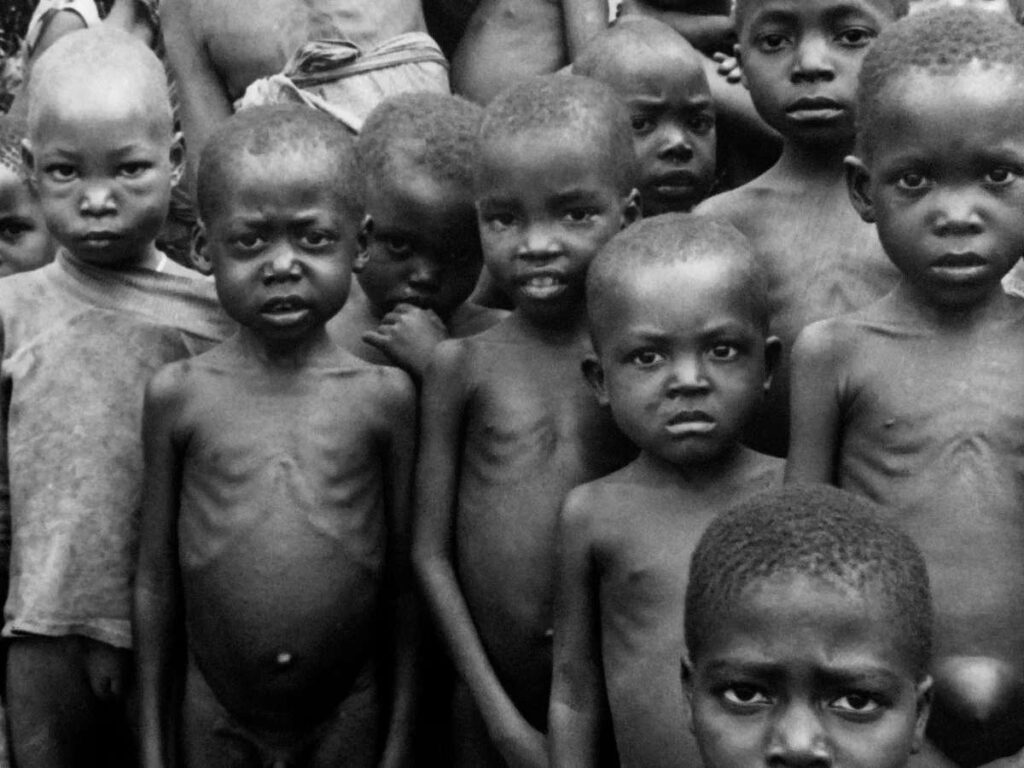

By 1968, extreme hunger began to spread. Disturbing images of dying Biafran citizens made it to international media. Pictures of malnourished children with swollen bellies and skeletal bodies sent chills down the spines of many viewers.

One of the most disturbing pictures from the war was that of a vulture on the ground, patiently waiting for a dying child to give up. The Biafran famine became a cause for global concern.

The body was so helpful to the war victims that they drew the anger of the Nigerian government, which accused them of supporting the Biafrans.

Despite the efforts of some foreign bodies to send aid at night, the supplies were not enough. The Nigerian government shook off international pressure and insisted on its strategy of starvation.

In January 1970, after a brave and surprising fight, the Biafrans gave up. General Ojukwu fled the country and surrendered to the Nigerian government.

But this time, over 2 million lives had been lost. Not just from bombs and bullets. Most of them died as a result of starvation and disease.

Global Reactions and Humanitarian Awakening

The Biafra oil conflict forced the world into a rare moment of reflection. Global audiences were taken aback by the level of dehumanization that the war’s victims suffered.

Pictures of suffering and dying people with eyes pleading for help triggered tears across the globe. More importantly, it provoked anger, sympathy, and action.

Charity organizations rallied around to save the oppressed population. Leading the efforts was the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

This body held meetings with both the Nigerian and the Biafran governments. As a result, they secured easy passage for relief materials, albeit for only a few months.

The ICRC even achieved a significant feat in its relief efforts. Its relief flights became the world’s largest civilian airlift since the Berlin airlift of the Cold War.

The body was so helpful to the war victims that they drew the anger of the Nigerian government, which accused them of supporting the Biafrans.

The World Council of Churches, alongside Caritas Internationalis of the Catholic Church, also played a significant role. Together they formed the Joint Church Aid (JCA).

The JCA rebelled against the Nigerian government’s airspace blockade. It organized nighttime flights laden with food and medication into Biafra.

The colonial powers ignored ethnic realities in assigning borders. The people were left to bear the consequences of the mistake.

Other notable interventions in the Biafran humanitarian crisis include efforts from Oxfam, UNICEF, the World Food Programme (WFP), the Lutheran World Federation, and the Save the Children Fund.

Doctors Without Borders originated unofficially as a response to the war. Bernard Kouchner and other French doctors who worked in Biafra for the ICRC left to form the organization.

They were dissatisfied with the Red Cross’s conservative style. The doctors believed that humanitarian workers should do more than just provide aid.

Workers should also “bear witness” and protest against the evil actions of the war they believe in. Aside from relief efforts and the courageous defiance against the Nigerian Biafran blockade, protests erupted, too.

Concerned students and corporate bodies came out in the streets across Europe and America, especially in defense of the starving children of Biafra.

The Fall of Biafra

Despite being overwhelmingly outnumbered and outgunned. The Biafrans proved to be a more formidable opponent than many people expected.

Most people, even Biafrans, were surprised that the war dragged on for as long as it did. However, as the months passed, the superior firepower of the federal forces began to take effect.

The Nigerian soldiers also benefited from the aid blockade and the starvation that followed. By the third year, the Biafrans were exhausted.

Nigerian forces continued to close in on the secessionists. They captured town after town, city after city, till their enemies were surrounded.

On January 15, 1970, Biafra surrendered. Colonel Ojukwu fled the country, and General Gowon took over, declaring “no victor, no vanquished.”

He reintegrated the Biafrans into Nigeria, but as a precaution, scrapped the regional government structure. Every part of Nigeria would be ruled directly from the center.

But one thing was sure, Nigeria would never remain the same.

Conclusion: Biafra’s Tragedy and Lessons

The story of the Biafran survival struggle is one of the unforgettable episodes in the history of African civil wars.

Nearly 60 years later, the scars of the Biafran civil war have remained. They run deep. There remains a significant gap in trust among the three major zones in the country. Many Igbos still feel left out of the Nigerian project.

To date, no person from the South-Eastern zone has emerged as president. This lack of representation at the highest office has remained one of the undeniable signs of post-war stigma.

To a large section of them, Nigeria is the product of a forced marriage that was brought about for economic reasons. Remove the oil, and many things will change.

The lessons from the Biafra War are pretty evident. The colonial powers ignored ethnic realities in assigning borders. The people were left to bear the consequences of the mistake.

The Nigerian Civil War is also a reminder of the destructive power of resource struggles. It highlighted the danger of unfairness and tribal bigotry. Despite all the negative consequences, the war ultimately proved beneficial to future generations.

The war strengthened humanitarian efforts for future conflicts. The world became more responsive to the plight of suffering people worldwide.

Do you think starvation is a justifiable war strategy? Share your thoughts.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Doctors Without Borders “Bearing Witness” → International Review of the Red Cross: (2012: Médecins Sans Frontières and the ICRC: matters of principle)

- Causes of the Conflict → Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa (2024: The Nigerian Civil War)

- The Colonial Mistake → History (2009: Civil War Breaks out in Nigeria)

- Bombing of Market Places and Hospitals in Biafra→UK Parliament (1969: Nigeria: Bombing Of Biafran Civilian Targets)