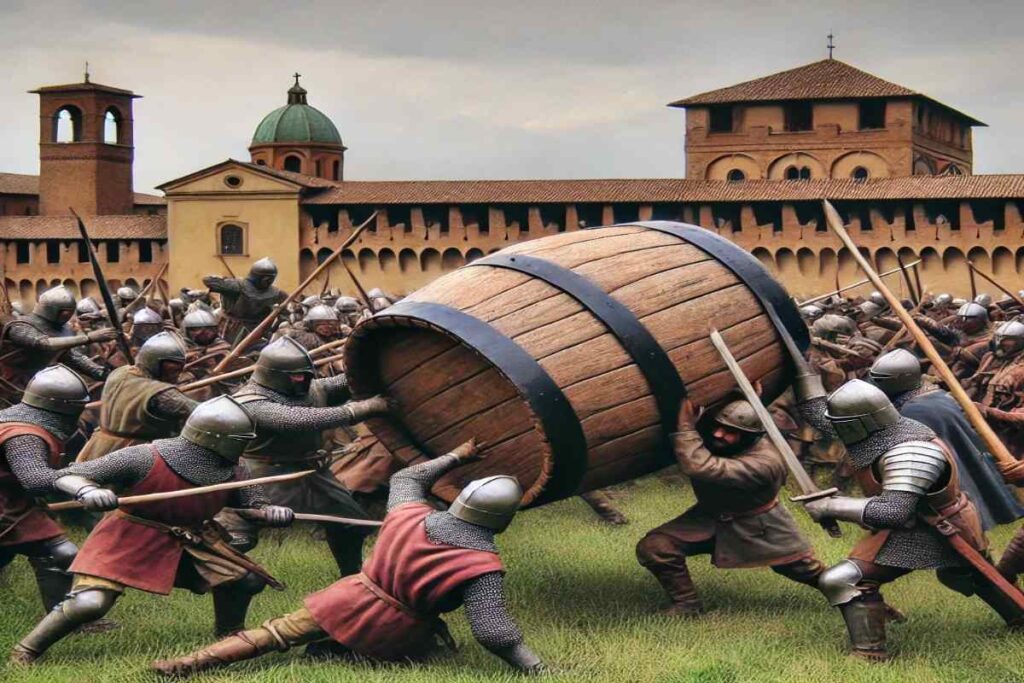

You won’t believe why two Italian city-states went to war some centuries ago. In 1327, Bologna and Modena drew swords against each other over a stolen bucket. No, not for wealth, territorial expansion, revenge, or any reason of the sort. But for a wooden bucket. This is the story of the war of the bucket, widely believed to be the most ridiculous war ever fought.

As silly and needless as it was, the war resulted in severe devastation. In the end, two thousand soldiers lay dead. One side clinched victory and maintained custody of the wooden bucket to date.

This Italian territory still displays its prize for the world to see. Today, people visit the beautiful city of Modena, Italy, if not for anything else, but to behold the wooden treasure that caused such a funny but tragic war.

The bucket hangs from the ceiling, suspended by an old metal chain at a bell tower in Modena. The lucky tower is also called Torre della Ghirlandina, and it is the main tower of a magnificent 12th-century cathedral.

Students have joked about stealing the bucket and taking it to Bologna. But the city of Modena isn’t ready to let go of the prize any time soon. They have put measures in place to ensure that nothing of the sort happens. But how did a wooden bucket become valuable enough to spark such a fatal war?

What Led to the War of the Bucket?

Modena and Bologna were two of the most notable cities in Northern Italy. This section of Italy was renowned for its urban nature. Although the two cities shared a lot in common, a battle of supremacy soon led to bad blood between them.

At the turn of the 14th century, a fierce competition ensued in Northern Italy, which was at the time, the most developed part of Europe. Each city-state tried to outdo the other in the areas of art and the sciences. This rivalry sparked a bitter feud between them that continued for decades.

To worsen the situation, a fight soon broke out between the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor. Both figures considered themselves the leaders of the church. As the two highly influential figures slugged it out, city-states soon began to align on either side.

The Modenese took sides with the Holy Roman Emperor while the Bolognese stood behind the pope. At this point, the tension between the cities reached a highly volatile point. Just a little spark was enough to cause an explosion. Not very long after, the spark came.

Both sides of the conflict had names. The pope’s group was referred to as the Ghibellines. Those loyal to the Holy Roman Emperor were the Guelphs. Their rivalry began in 1075, resulting in a number of battles. Although both sides stopped physical combat in 1122, a cold war continued to brew underneath.

At the turn of the 14th century, the Guelphs began to enjoy the upper hand. However, this dominance didn’t last for long as they soon suffered a devastating factionalization that pitted the whites and blacks against each other. This negative turn gave the Ghibellines an unexpected advantage.

Both parties weren’t just people who answered a common name. They were passionate about their support and were ready to prove it. The Ghibellines of Modena struck first.

In a bid to assert their superiority, a group of men from Modena snuck into Bologna at night. They didn’t come to fight. All they needed was to steal something significant. They chose to steal a wooden bucket from a well in a bid to mock the Bolognese. It all went as planned.

Bologna woke up the next morning to the news that the Modenese had infiltrated their city and made away with their wooden bucket. It was an oaken bucket used at the municipal well. Despite the item having little or no value to them, it wounded their fragile ego, exactly as the Modenese wanted.

Like angry lions, the Bolognese demanded the return of their bucket. Modena refused, daring them to do their worst. War became inevitable. The Bolognese then put together an army of 32,000 fighters who would march into Modena, recover their bucket, and destroy anyone who stood in their way.

The Bolognese had the full backing of the papacy. Pope John XXII lent his voice to the debacle, announcing the chief magistrate of Modena a heretic.

In Modena, the people were worried. They could only assemble a paltry 7,000-strong army. This was less than 25% of the Bolognese force.

But the Modenese army wasn’t completely disadvantaged. While their army comprised professional and well-trained German soldiers, the Bolognese presented a multitude of able-bodied men with no military experience. No one could tell what factor, between skill or number, would decide the winner.

The Modenese weren’t going to wait for their foes to invade their land. Modena’s military commanders ordered their army to meet their enemies halfway. Both armies came face to face outside the town of Zappolino. November 13, 1325, was the day that hosted this unbelievable war.

After multiple hours of a gruelling and bitter clash, both sides suffered the deaths of a thousand soldiers. Collectively, the silliest war ever fought claimed two thousand precious souls. As it turned out, competence rather than number was the deciding factor.

The Bolognese were the first to cave in. They beat a retreat and scampered back to base. The Modenese gave them a hot pursuit, chasing them into their city. In mockery of their enemies’ retreat, it was reported that the Ghibellines of Modena had a fun time as their enemies watched from inside the city.

The Modenese taunted their foes with a “palio” – a kind of pocket decathlon. Reports also state that the Modenese stole a second bucket, adding insult to injury. However, some accounts state that the wooden bucket was only stolen after the war and not before.

Whatever the case, a wooden bucket was involved. Although most people believe that an oaken bucket was solely the cause of the War of the Bucket, the Modenese and Bolognese were already at each other’s throats for many decades before. The theft of the bucket was only a spark that produced the fires of war.

After their victory, the Modenese thought about invading Bologna and taking over the city. However, they soon learnt that this was a tall order. The Bolognese enjoyed the protection of well-fortified city walls. The best option for both parties going forward was to reach a truce.

The two cities finally signed a peace deal in January 1326. This deal kept both parties away from war for only a few years. Hostilities between them later resumed, which lasted for a massive 200 years until they both, alongside the nation of Italy, fell to the Spanish in 1529.

However, in the midst of all these, one issue continued to linger. The possession of the wooden bucket. The Modenese never returned the contentious bucket. Instead, they hung it on the bell tower of one of their popular cathedrals – the Torre della Ghirlandina.

But the original bucket has been removed and replaced by a replica. The original now hangs at the Palazzo Comunale, where it testifies to the funny but fatal war story to date. Of course, the Bolognese aren’t amused about this. They wouldn’t hesitate to recover possession of the prized bucket as soon as they had the opportunity.

The War of the Bucket has also provided material for many literary giants. For example, Italian writer Alessandro Tassoni wrote a mock piece about the war. He titled the 1622 poem “La Secchia Rapita” or “The Sad Kidnapped Bucket.”

In 1772, more than a hundred years later, notable composer and one of Mozart’s rivals, Antonio Salieri, gave the same title to a comic opera he put together to tell the story of the war.

More than 700 years later, the story has survived from one generation to the next. It has also maintained the top spot in the list of the most ridiculous and needless wars ever fought.