Let me take you on a journey into an era you’ve only read about in books or seen played out in movies: the Spanish conquest of the Americas. This was one of the most transformative events in world history. It all began in 1492, with Christopher Columbus’ voyage under license from Queen Isabella I of Castile.

History has it that Christopher Columbus made four voyages to the Americas between 1492 and 1504. During these expeditions, the Genoese mariner explored various Caribbean islands, including Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Cuba, and Puerto Rico.

Although Columbus is often credited with “discovering” the Americas, his voyages opened up the region to subsequent European exploration and colonization. During this period, Spain rapidly expanded its influence, conquering vast territories and establishing a colonial empire that lasted for centuries.

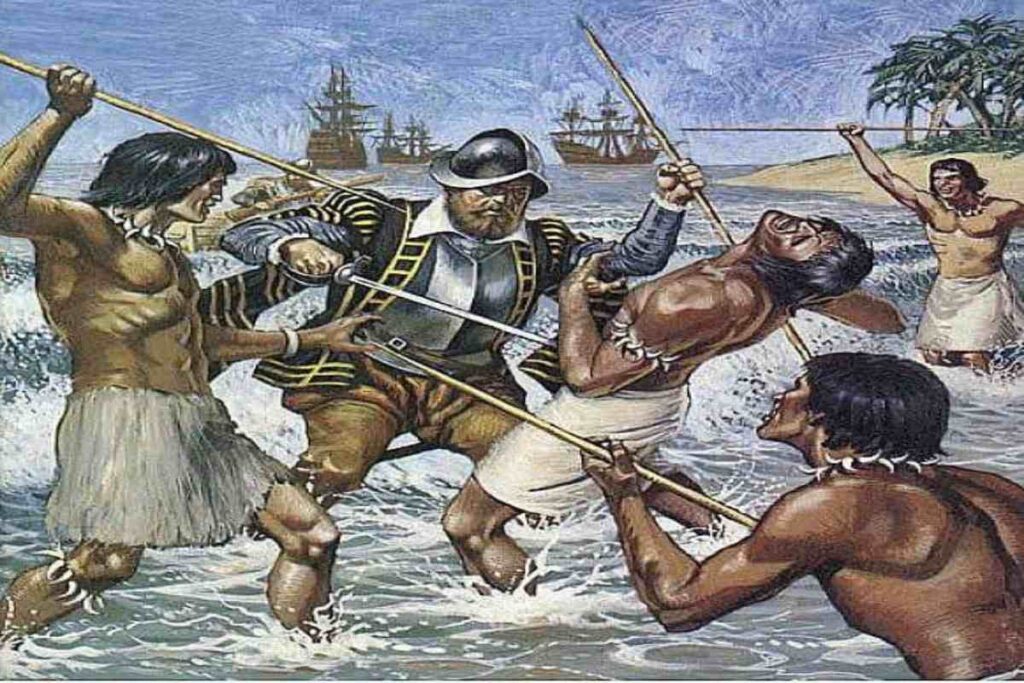

The Spanish conquest of the Americas saw the destruction of powerful indigenous empires and brought people into the Catholic Church peacefully and by force, when need be. And it all started with an exploration.

The Era of Exploration

During the late 15th century, European nations sought new trade routes to Asia. The Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Isabella I of Castile and her husband, Ferdinand II of Aragon, financed Columbus’ voyage in 1492. Columbus and his crew departed from the port of Palos de la Frontera on 3 August 1492.

However, on 12 October 1492, instead of reaching Asia, the Genoese mariner and his crew made landfall in the Western Hemisphere, the Caribbean. In 1493, the permanent Spanish settlement of the Americas began.

Between 1492 and 1504, Columbus’ voyages explored the Caribbean, claiming vast lands for Spain. As a result, the crown created civil and religious structures to manage the vast territory. Spanish men and women settled in great numbers in places with dense indigenous populations and valuable resources for extraction.

Isabella and Ferdinand pursued a policy of joint rule of their kingdoms, but they remained separate due to the political nature of their union. They ruled their respective kingdoms jointly, uniting Castile and Aragon into what became the foundation of modern Spain.

However, there were times when they governed separately, with Ferdinand spending more time in Aragon and Isabella in Castile, as each kingdom retained its own laws and administration. Despite these separations, they maintained a strong political and personal partnership.

Like the Catholic monarchs, the Kingdom of Portugal authorized a series of voyages down the coast of Africa. When they rounded the southern tip, they were able to sail to India and further east. Portugal’s early and successful explorations to India spurred Spain to follow suit.

The explorations saw the Kingdom tap into the lucrative spice trade, which paved the way for more explorations. Spain sought similar wealth and authorized Columbus’ voyage west. Once the Spanish settlement in the Caribbean occurred, Spain and Portugal formalized a division of the world in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas.

The treaty divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile. Under the treaty, the lands to the east would belong to Portugal, and the lands to the west to Castile. This granted Spain most of the Americas.

By the 1500s, Spanish conquistadors launched expeditions and ventured into the mainland of the Americas. Spaniards spent over 25 years in the Caribbean, where their initial high hopes of dazzling wealth became a wild goose chase.

The Conquest of the Aztec Empire

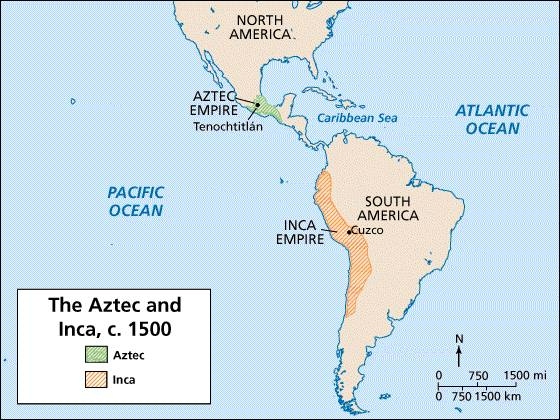

The Aztec Empire, a powerful Mesoamerican civilization centered in Tenochtitlán (modern Mexico City), was conquered by a settler in Cuba, Hernán Cortés, in 1521. Cortés received authorization in 1519 to lead an expedition to the far western region. The invasion of Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec Empire, marked the beginning of Spanish dominance in the region and the establishment of New Spain.

Led by Moctezuma II, the Aztec Empire had established dominance through military conquest and intricate alliances. Backed by military force, the Aztecs had a way of keeping subordinate rulers compliant. However, their hegemonic system of governance was inherently unstable, as any alteration in the status quo would see it all go up in flames.

Upon arriving at the empire, Cortés sought the help of indigenous allies who opposed the Aztecs. The Spaniards made alliances with tributary city-states of the Aztec Empire and their political rivals, particularly the Tlaxcaltecs and Tetzcocans, a former partner in the Aztec Triple Alliance. They also persuaded the leaders of Aztec vassals to unite with them against the Aztecs.

One of the most important contributors to the Spanish success was a multilingual Nahua-speaking woman known to the Spanish conquistadors as Doña Marina. She became famous for her role as an interpreter and intermediary for Hernán Cortés during his conquest of the Aztec Empire. By August 1521, after months of siege and smallpox outbreaks, Cortés and his forces had defeated the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II.

This conquest marked the beginning of Spanish rule in the region. It led to the establishment of New Spain (Nueva España) as a Spanish colony, with Mexico City built over the ruins of Tenochtitlán.

The Inca Empire Falls

The Inca Empire, which ruled over the Andes, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. However, when the Spanish arrived, it became weakened by civil war and disease. Francisco Pizarro, a Spanish conquistador, led the conquest against the Inca Empire.

In 1532, Pizarro arrived in the Andes with a small force. At the time, the Incas were divided after a civil war between Atahualpa, the ruling Inca emperor, and his brother Huáscar. In November of the same year, despite being outnumbered, Pizarro and his forces ambushed and captured Atahualpa at the Battle of Cajamarca.

By 1533, Pizarro’s forces had executed Atahualpa, and the Spanish had marched on Cuzco, the Inca capital. After the emperor’s death, Cuzco fell easily. Years later, in 1572, Pizarro and his forces conquered the last Inca stronghold, Vilcabamba, completing the Spanish takeover. This conquest opened the door for Spanish colonization and the extraction of vast wealth from the Andean region, especially the silver mines from Potosí.

What if the Aztecs Had Successfully Resisted Spain?

Imagine a world without Spanish as a global language. A world where history takes a different path, and the Aztecs and Incas had united against the invasion of Spain, limiting the spread of the language. Have you wondered what would have happened if the empires had adapted their warfare and built empires that could resist European colonization?

The year is 1520, and Hernán Cortés, after receiving authorization to lead an expedition into the Aztecs, arrived at the empire. In our timeline, the invasion of Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec Empire, marked the beginning of Spanish dominance in the region and the establishment of New Spain. However, unlike our history, the Aztecs had a stable system of governance that was unshakeable even by the Spanish invasion.

The emperor, Cuauhtémoc, had learned of Cortés’ arrival and had heard of his escapades, especially the massacre at the Templo Mayor. In May 1520, on the day of the Feast of Toxcatl, a troop of Spaniards assaulted the Templo Mayor, the main temple in Aztec-Tenochtitlan. After learning of Cortés and his force’s intentions, Cuauhtémoc refused to let the Spaniards gain any more ground.

Cortés sought the help of indigenous allies who opposed the Aztecs. He also tried to make alliances with tributary city-states of the Aztec Empire and their political rivals, particularly the Tlaxcaltecs and Tetzcocans. However, instead of allowing Moctezuma to be manipulated, the Aztec nobility united under a war council, focusing on expelling the Spanish invaders.

Smallpox still ravaged the Aztecs due to the influx of the Spaniards, but instead of surrendering, they quarantined infected areas and trained new warriors. Under orders from Cuauhtémoc, the Aztecs trapped the Spaniards, adapted their warfare, and forced Cortés to retreat.

However, he had another thing coming his way. The Aztecs broke off the causeways and trapped the Spaniard in the burning city of Tenochtitlán, cutting off his retreat. Seeing that the Spanish were doomed, the Tlaxcalans switched sides.

Aware that this was the end of the road for him, Cortés became weighed down. As a result, he drowned in Lake Texcoco along with most of his men, with the rest captured and forced into teaching the Aztecs gun-making. So, Nahuatl remains the language of the Aztec empire.

The Inca Empire Does Not Fall

Like Cortés, Francisco Pizarro marched into the Andes, expecting an easy conquest in 1532, but you won’t believe what happened next. Instead, Pizarro found an empire ready for him. The emperor, Atahualpa, having heard of Cortés’ fate in the hands of the Aztecs, refused to meet the Spaniards on open ground. Instead, he lured Pizarro into the high mountains, where thin air and ambushes devastated the invaders.

History has it that the Incas negotiated with the Spaniards, but picture a world where they did not. Instead, they launched night raids on Spanish encampments, cutting off their supplies. Unused to the high mountains and altitudes, Pizarro’s men began to die—not just from Inca weapons, but from the cold and starvation.

With Pizarro’s military strength dwindling, the Quechua armies, led by Atahualpa’s best generals, crushed the Spaniards in a final battle near Cajamarca. Pizarro was captured and paraded through Cusco before his execution. Afterward, the Inca Empire centralized its power, creating a professional military and adopting Spanish steel weapons and horses.

By 1550, the surviving Spanish holdouts in the Caribbean were wiped out by the Inca-Aztec alliance. The two great civilizations, who have formed an alliance and agreed to support each other against any future European invasions, are modernizing rapidly.

Meanwhile, in Europe, Spain reels from its losses. Without American silver from Potosí, the Spanish economy collapsed. The Crown, unable to afford new expeditions, abandoned its ambitions in the Americas, shifting focus to Asia and Africa.

By 1700, the world looked completely different, with Nahuatl and Quechua becoming the dominant languages of the Americas instead of Spanish or Portuguese. By the start of the 19th Century, when the Industrial Revolution began, it was not just England and France leading global progress—the Inca-Aztec Alliance had steam engines, railroads, and guns of its own.

Tenochtitlán remains a massive capital, while Cusco rivals London in wealth and architecture. Today, instead of Spanish being the dominant language of Latin America, Nahuatl and Quechua are spoken from Mexico to Argentina. Envision this: as the world is changing, the spirits of the Aztec and Inca live on, their tongues unbroken, their lands untamed, and their people free.

You Might Also Like:

The Development of Written Language (c. 3300 BCE – Present)

The Evolution of the Human Flight

The Unusual Story of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui)