Once upon a time, Portuguese seafarers in the fifteenth century set sail toward the African coast and the Atlantic islands but landed in an unknown land. As an extension of the Portuguese Reconquista, which saw all the cities under Muslim control in the Algarve captured in 1249, they began to expand from a small area of the Iberian Peninsula to seizing the Muslim fortress of Ceuta in North Africa.

The year was 1500, and the Portuguese, driven by the promise of riches, had already reached India and were continuing to expand their trade empire. They traveled down from India, across the South Asian subcontinent, and into the Atlantic islands off the coast of Africa. The European kingdom sought gold, ivory, African slaves, and high-value goods in the African Trade. Let’s dive into how it all began.

The Portuguese’s Arrival

The Portuguese Colonization of Brazil began on April 22, 1500, when a fleet led by explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral landed on the coast of Brazil and took possession of the land in the name of the king. This marked the beginning of over three centuries of Portuguese rule in the region. History has it that Cabral was leading a large fleet of 13 ships and more than 1,000 men following Vasco da Gama’s way around Africa to India.

For context, Vasco da Gama was a Portuguese explorer and nobleman and the first European to reach India by sea. Before the Portuguese discovered Brazil, a series of treaties existed between the monarchs of Portugal and Castile (Spain). These treaties resulted from the Portuguese sailings down the coast of Africa to India and the voyages of the Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus, who was sailing for Castile.

The most assertive of these treaties was the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494. This treaty created the Tordesillas Meridian, dividing the world between the two kingdoms. The treaty maintained that all land discovered or to be discovered east of that meridian was to be the property of Portugal, and everything to the west of it went to Spain.

Upon his arrival, Cabral discovered that no one in his convoy spoke the indigenous language of the people of Brazil. In a bid to avoid violence and conflict, he used music and humor as forms of communication. The Portuguese explorer learned from the experience of Spanish navigator Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, who arrived on the northeastern coast of Brazil, to treat communication with the utmost priority.

Pinzón deployed armed men ashore with no means of communicating with the indigenous people, which saw one of his ships and captains captured by indigenous people and eight of his men killed. However, Cabral safely entered and left Brazil in ten days despite having no means of communication with the indigenous people there. Before leaving the new-found land, Cabral left two degredados, criminal exiles, in Brazil to learn the native languages and to serve as interpreters in the future.

The Early Stages of Colonization

After Cabral left Brazil, the Portuguese focused on their expeditions in Africa and India, showing little interest in Brazil. Between 1500 and 1530, Portugal carried out a few expeditions in the new land to chart the coast and export pau-brasil, brazilwood. At the time, Europeans used this wood to produce a valuable red dye for luxury textiles.

To extract brazilwood from the tropical rainforest, the Portuguese and other Europeans relied on the work of the natives, who initially worked in exchange for European goods like mirrors, scissors, knives, and axes. During this early stage of the Portuguese Colonization of Brazil, the Portuguese relied on the help of the Europeans, the degredados, who lived with the indigenous people and understood their languages and culture.

Over time, the Portuguese realized that other European countries, especially France, were also sending excursions to the land to extract brazilwood. Despite initial disinterest in colonization due to Portugal’s focus on lucrative trade routes in Asia and Africa, the increasing presence of European rivals in the region spurred the Portuguese Crown to establish a more permanent presence in Brazil by the 1530s.

Worried about foreign invasions and hoping to find mineral riches in Brazil, the Portuguese crown decided to send large missions to take possession of the land and expel the French. In 1530, an expedition led by Martim Afonso de Sousa arrived in Brazil to patrol the entire coast, eject the French, and create the first colonial villages like São Vicente on the coast.

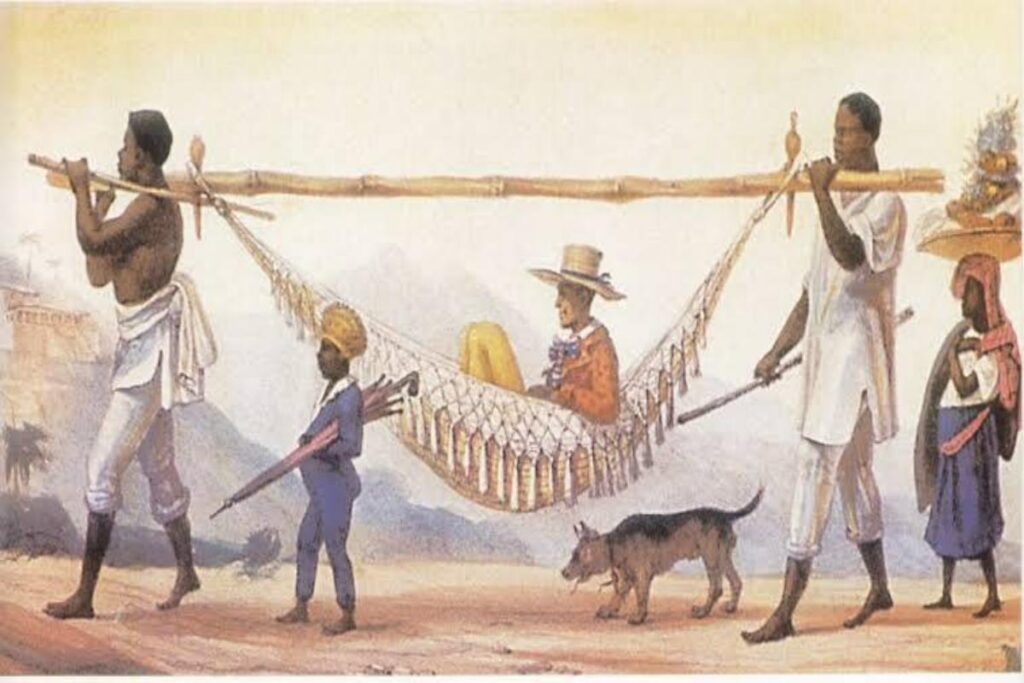

Brazil’s Colonial Society

Unlike the Inca and Aztec empires, Brazil was not home to larger civilizations. So, Portugal found itself in a land without social structure. Consequently, the relationship between the Portuguese and the Brazilian colony was very different from the relationship of the Spanish to their possessions in the Americas. While Portugal saw the Brazilian colony as a commercial asset that would facilitate trade between the Portuguese and India, Spain saw its colonies as a place to be settled to develop a society.

However, the Portuguese crown found that having the colony serve as a trading post was not enough to regulate land claims in the Americas, so it decided that the best way to keep control of their land was to settle it. Thus, the land was divided into fifteen private, hereditary captaincies, each granted to a single donee, a Portuguese nobleman who was given the captain General title.

By the mid-16th century, the Portuguese introduced sugarcane plantations, primarily in the northeastern regions such as Pernambuco and Bahia. The sugar economy flourished, making Brazil one of the world’s largest sugar producers. However, the discovery of Minas Gerais, a state in Southern Brazil known for colonial-era towns dating to the country’s gold rush, in the late 17th century led to a gold rush.

The discovery of gold was met with enthusiasm by Portugal, attracted thousands of settlers, and shifted economic power from the sugar-producing northeast captaincies. By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there was growing dissatisfaction with Portuguese rule, inspired by the American and French Revolutions. But by then, the Portuguese colonization had left a lasting impact on Brazil.

Unlike other Latin American nations, Brazil’s independence was relatively peaceful. However, tensions began to brew after the Portuguese royal family, led by Dom João VI, fled to Brazil in 1808 to escape Napoleon’s invasion of Portugal.

Upon Napoleon’s defeat, pressure began to mount for Dom João VI to return to Portugal, so he left his son, Dom Pedro I, as regent. When the Portuguese Cortes (parliament) attempted to reduce Brazil back to colonial status, the indigenes resisted. Left with no choice, Dom Pedro I declared Brazil’s independence near the Ipiranga River in São Paulo on September 7, 1822.

Portuguese remains Brazil’s national language, and elements of Portuguese culture, religion, and legal systems are deeply embedded in Brazilian society. Now, imagine for a second that Spain had claimed Brazil in the early 16th century. What would have happened if Spain had violated the 1429 Treaty of Tordesillas or if the Treaty was not in place at all?

What if Brazil Was Colonized by Spain Instead?

Imagine a Brazil where the official language is Spanish, and instead of a united nation, the country is divided into smaller independent Spanish-speaking nations. In this world, instead of the Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral landing on the coast of Brazil, Genoese Mariner Christopher Columbus did instead.

Columbus claimed the land for Spain before Portugal had the chance. Of course, this altered the Treaty of Tordesillas, giving Spain an even greater hold over South America. Unlike Portugal, Spain used a different model for its colonies in the Americas.

As a result, the vast territory became divided into multiple smaller colonies, much like Spanish America. Spain’s system of viceroyalties led to the creation of separate administrative regions, such as a Viceroyalty of Brazil and divisions between the Amazon, the Northeast, and the South.

Unlike the centralized rule of the Portuguese crown, Spain’s more fragmented approach resulted in different regions gaining independence separately, leading to multiple nations instead of a unified Brazil. So, instead of being called Brazil, each nation had its own name, such as Amazonia, Gran Paraíba, Nueva Bahía, Río Dorado, and Guayania.

Like in most of its colonies, Spain prioritized mineral extraction. As a result, the Spaniards quickly discovered major silver and gold deposits, like in Potosí (Bolivia). This made Brazil a major mining center.

The nations created from then-Brazil were heavily influenced by Spanish traditions rather than Portuguese, and Spanish became the dominant language instead of Portuguese. Nations like Gran Paraíba, Nueva Bahía, Río Dorado, and Guayania resembled Buenos Aires and Lima, with strong architectural and political influences from Spain. Under Spanish colonization, Brazil was not unified as we know it.

You Might Also Like:

The Development of Written Language (c. 3300 BCE – Present)

The Evolution of the Human Flight

The Unusual Story of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui)