Resilience. Throughout history, humanity has demonstrated resilience. Time and again, the human race has been locked in wars that threatened to upend its very existence. From the cradle of civilization, pandemics have swept through humanity, leaving tears, anguish, and pain in their wake.

However, they have also sparked some of the most impressive medical discoveries. The history of pandemics and medical breakthroughs is not just one of suffering; it is a tribute to the resilience, ingenuity, and relentless pursuit of human survival.

With the medical advancements in the 21st century, one can only wonder how humans survived long before the microscope. The plague of Athens (430 BCE), one of the earliest known pandemics, wiped out a quarter of the city’s population and remains a mystery to this day.

Was it typhoid fever, chicken pox, or Ebola? We may never know. The plague of Justinian (AD 541–549), an epidemic that afflicted the entire Mediterranean Basin, Europe, and the Near East, severely affecting the Byzantine Empire, also killed about a fifth of the population in the imperial capital.

The Antonine Plague (165-180 CE), likely smallpox, decimated the Roman Empire and changed the course of history. These early pandemics, misunderstood and terrifying at a time when humans still bathed in the Euphrates, drove civilizations to seek answers, setting the stage for medical advancements.

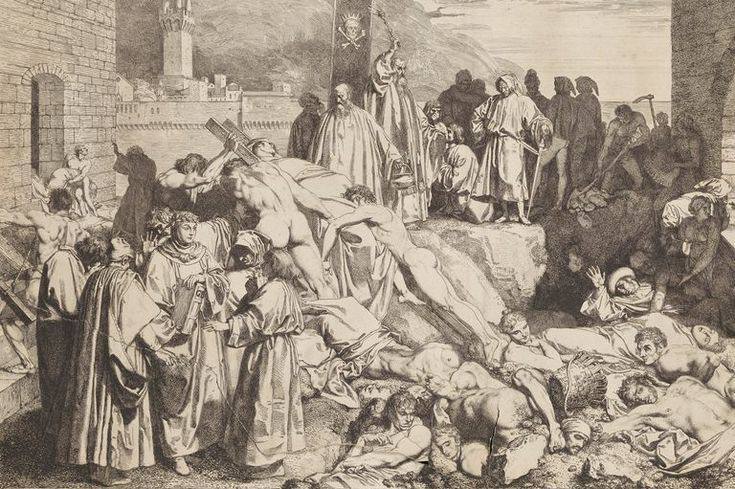

Similarly, the horror of The Black Death, one of history’s deadliest pandemics, shook the core of humanity, having killed over 50 million people. The terrifying illness, carried by fleas on black rats, spread from person to person as pneumonic plague, affecting nearly 50% of Europe’s 14th-century population. However, amid the disaster, there was learning.

The Black Death reshaped Europe’s social structure as the realization that disease could spread through contact sparked the earliest concepts of public health, paving the way for the first quarantines. Had humanity made medical breakthroughs early enough, could these horrors have been averted? Again, we may never know.

Following humanity’s victory against the Black Death, smallpox swept through civilizations like ghosts in the night. For centuries, smallpox was unbeatable. It ravaged populations and wiped out cities, leaving early civilization in ruins. With an overall fatality rate of 40 %—50 % in children younger than 1 year and the fatality rate for flat or late hemorrhagic type smallpox at 90% or greater and nearly 100%, smallpox became a nemesis.

ALSO READ: THE GREAT EMU WAR

However, in 1796, English physician Edward Jenner noticed that milkmaids who had contracted cowpox didn’t get smallpox. He demonstrated the effectiveness of cowpox to protect humans from then-deadly smallpox, and his curiosity led to the first-ever vaccine. This breakthrough changed medicine forever, proving that humans could fight back against nature.

On March 26, 1806, the Swiss canton Thurgau became the first state in the world to introduce compulsory smallpox vaccinations by order of the cantonal councilor Jakob Christoph Scherb. Afterward, vaccination continued in industrialized countries as protection against reintroduction until the mid to late 1970s.

After winning the war against smallpox, humans heaved a sigh of relief, only to be hit in the face with cholera outbreaks in the 19th century. Cholera became a disease of global importance in 1817. The first cholera pandemic occurred in the Bengal region of India, near Calcutta, and started in 1817 through 1824.

It was carried by tradesmen along shipping routes, and it rapidly spread to the port of Hamburg in northern Germany. It made its first appearance in England, in Sunderland, in 1831. In 1832, it arrived in the Western Hemisphere, with millions of deaths documented.

Since there were no major medical breakthroughs at the time, many believed in the miasma theory that bad air caused the disease. With a mortality rate of 50-60%, cholera scourged the human race. However, when the going gets tough, the tough get going. Humans, again, did not falter in the face of this horror. In 1845, Physician and pioneer medical scientist John Snow found a link between cholera and contaminated drinking water.

This discovery laid the foundation for epidemiology, as he demonstrated that human sewage contamination was the most probable cause of two major epidemics in London. Though devastating, the cholera outbreak gave John Snow the title of the father of epidemiology and changed how humans combat outbreaks. The medical breakthrough against cholera gave the human race an upper hand against whatever nature had in store for it.

For those who survived the deafening boom of WW1 as the distant echo of victory rang in their ears, an even deadlier battle began. The Spanish flu. The earliest documented case was in March 1918 in Kansas, United States, with further cases recorded in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom in April. This pandemic infected around 500 million people, one-third of the world’s population, cutting through the remaining shred of hope for survival.

However, unlike the previous pandemics, humans had begun to understand viruses. They had learned from past mistakes, and what was left of the human race had grown a tough skin against horrific pandemics. Scientists faced the pandemic head-on, raced to develop flu vaccines, and public health campaigns took root.

While systems for alerting public health authorities of infectious spread did exist in 1918, they are nothing compared to what we have now. Nevertheless, actions were taken. Maritime quarantines were declared, social distancing measures were also introduced, and schools, theatres, and places of worship were closed, saving many lives.

In the 1980s, another mysterious disease that attacks the immune system emerged, killing millions and sparking fear worldwide. The first news story on the disease appeared on May 18, 1981, in the gay newspaper New York Native. HIV/AIDS was first clinically reported on June 5, 1981, with five cases in the United States. In the early days, there was no official name for the disease, which ravaged the community of injecting drug users and gay men.

Initially referred to as the “4H disease,” the syndrome seemed to affect heroin users, homosexuals, hemophiliacs, and Haitians. However, after determining that it was not isolated to the gay community, the term AIDS was introduced. After multiple trials and errors, by the 1990s, antiretroviral therapies transformed HIV from a death sentence into a manageable condition. Today, humans stand on the brink of a cure, a testament to our persistence and resilience over time.

When COVID-19 struck in 2019, the world was thrown into chaos. Although unprepared, humans were not uninformed. Swift actions swung in place, social distancing rules, mask-up campaigns, and economic shutdowns, and the world came to a halt.

While the earliest men were armed with superstition, herbal remedies, and trial-and-error survival tactics, the 21st-century men wield cutting-edge science and advanced medical technologies. Yet, the human race recorded millions of deaths worldwide again.

As the everyday man got busy with the “buss it” and “flip the switch” challenges on TikTok, scientists got to work. Within a year, mRNA vaccines were developed, the fastest in history, and social distancing became the order of the day.

This unprecedented medical breakthrough showcased the power of global collaboration, science, and technology. However, it also ignited controversy, skepticism, and controversial theories about medicine, government involvement and control, and personal freedoms.

Was COVID-19 engineered in a science laboratory? Was it a government tool to reduce the worldwide population? Did COVID-19 leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology? These questions remain unanswered, but the hearing of Former top U.S. infectious disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci shows that the hypothesis of a lab leak as the origin of a pandemic that killed millions worldwide can no longer be dismissed today as a “conspiracy theory.”

Could humans eradicate pandemics forever? Or will nature always stay one step ahead? As history has shown, one of humanity’s greatest strengths is curiosity, the driving force behind every medical breakthrough. While the battle between humans and disease is not over, with resilience, we continue to fight—and win.