A fierce war is raging between the United States and China. Since early 2025, the world has been amused yet horrified as the two giants have slugged it out in a battle of supremacy. But it’s not a contest of bombs, tanks, or fighter jets. It’s a trade war.

Interestingly, trade wars are nothing new. They are mostly fought through import levies or tariffs. The U.S., as well as other nations, has a history of fighting other countries over tariffs.

Let’s go back into the past to examine some of the notable trade wars that have happened in America’s history, beginning with the Smoot-Hawley trade wars. While there are also non-American trade wars worth mentioning, let’s examine the state of the current impasse.

Hostilities began on February 1, 2025, after United States President Donald Trump announced a 10% income tax on all goods coming into the country from China.

At the same time, the trigger-happy and newly re-elected 47th president targeted neighbors, Canada and Mexico, with 25% levies on all imports. This unexpected tariff policy came into effect on February 4, 2025, barely a month after the billionaire businessman took office.

Although Trump put a hold on the Canada and Mexico tariffs following scheduled negotiations, the China tariffs took effect on February 4. Irked by the development, China swung into action almost immediately. On the same day, the Asian superpower announced a slew of retaliatory moves.

China imposed new duties on a number of American products. This included a 15% tariff on liquified natural gas and coal products and a 10% charge on agricultural machinery, heavy-duty engine vehicles, and crude oil from the United States.

With both countries taking turns to retaliate, tariffs between the two world powers have so far climbed up to 145% as of April 21, 2025. But China, Mexico, and Canada aren’t the only countries affected by Trump’s move to level the playing field and stop the United States from being “ripped off.”

The U.S president, later on April 2, 2025, announced retaliatory tariffs on all countries of the world. This included a baseline tariff of 10% and extra levies on countries with a trade surplus over America. While many countries accepted the new charges, others staged a revolt.

The Asian superpower is one of the countries that have fought back against the new tariff onslaught from the United States. Relations between the two countries have also dipped sharply since then.

Reflecting the severity of the worsened relations, China has sounded a warning to other countries against negotiating with the United States against its interests. China said this in a statement made by its Ministry of Commerce spokesperson.

The spokesperson made this warning in response to widespread reports of the United States pressuring other nations to isolate China. According to the statement, China will “take countermeasures in a resolute and reciprocal manner” against any country that bends to the United States’ alleged plan.

Many believe that the United States had the intention of collaborating with other nations against China. The aim of this alleged secret plan is to whittle down China’s upper hand in the global manufacturing arena.

Meanwhile, Trump has kept the door open in hopes of a negotiation. But China will have to swallow a massive chunk of pride to tap out of the United States’ grip.

Again, trade wars aren’t new. Neither is Trump the first United States president to start one. Let’s go down memory lane to the 1930s when the first trade war of this kind took place.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930)

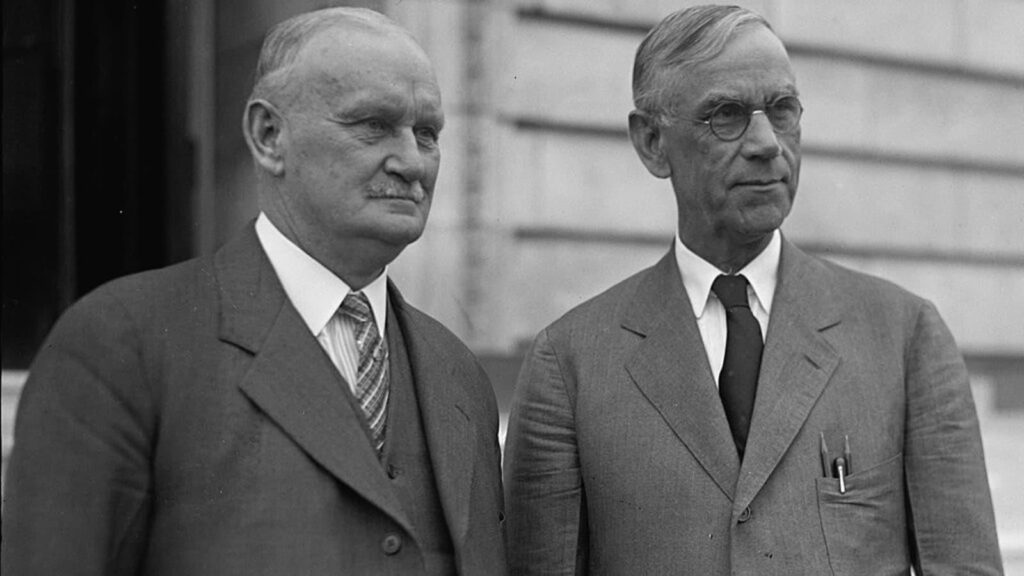

Back in the 1930s, in the thick of the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Act into law. Named after its sponsors, Senator Reed Smoot and Congressman Willis C. Hawley, the Act became law in June 1930.

The aim of the legislation was to give the agricultural sector a massive boost by increasing tariffs on foreign goods. The Act, which was signed shortly after the stock market crash of 1929, was designed to encourage customers to purchase made-in-America products.

The logic behind it was pretty simple. Increased tariffs will raise the market prices of imported products, thereby forcing American consumers to stick with locally made goods.

To make sure the plan didn’t disappoint, the Act raised average tariff rates from 38% to about 60%. Over 20,000 imported goods were affected by the new policy. Of course, America’s trading partners were far from impressed, and allies soon turned to enemies.

Retaliatory tariffs soon began to emerge. Countries such as Canada, France, and Spain soon increased their tariffs on American goods. The trade war wasn’t good for the global market. World trade dropped by over two-thirds.

Another result of the trade war was a slump in American exports. Notably affected was the agricultural sector, which was one of the major pillars of the United States’ economy. As a result, America suffered a cobra effect as its economy took an even bigger hit, which also sent ripples across the globe.

The Anglo-Irish Trade War (1932)

Trade wars aren’t exclusive to the United States. Other countries have had their share of tussles over commercial matters. The Anglo-Irish trade war of the 1930s happened just after the Smoot-Hawley trade war.

From 1932 to 1938, Britain and Ireland slugged it out on the trading ground. At the time, the Irish government had been repaying loans handed to its farmers by the United Kingdom. These payments, called land annuities, stemmed from loans the UK gave to Irish tenant farmers for land purchases at the end of the 19th century.

These annuities were paid regularly until a new leader, Eamon de Valera, discontinued them in 1932. He justified his decision by tagging the payments as unfair, given that the Irish nation was now an independent state.

Irked by this move, the British government slapped the Irish with higher tariffs on its agricultural exports. These levies brought the Irish economy to its knees, given that the UK received more of Ireland’s exports than any other state. But the Irish were not about to surrender.

Ireland responded with retaliatory tariffs. She increased the levies on British goods coming into its shores. However, she was also greatly affected by this tariff hike as her economy survived on British exports. Ireland then made moves to reduce its reliance on British exports.

However, the dispute came to an end in 1938 at the negotiation table. Ireland agreed to pay all the pending land annuities in a fell swoop. Subsequently, both parties brought down their tariffs and became trading allies again.

The Chicken War (1960s)

If you are guessing that this trade war had something to do with birds, you are correct. In the 1960s, the United States and a number of European countries fought over trade. The U.S. and the European Economic Community (EEC) disagreed over poultry tariffs.

Following an increase in poultry exports from the United States to Europe in the late 1950s, the EEC decided to increase its tariffs. Poultry farmers struggled to find a market for their produce due to a flood of cheaper American chickens. They then cried to their governments for help.

In response, the European authorities, particularly France and Germany, in 1962, raised the levies on American poultry. This move angered the United States government, led by John F. Kennedy.

The President responded by hiking tariffs on a number of key European products such as Volkswagen vehicles and French Brandy. This tariff on Volkswagen vans soon expanded to light trucks of other brands.

These developments greatly harmed the trade relationship between the U.S and these European countries. Interestingly, the tax on light trucks is still in effect to date.

The United States and Canada Lumbar Trade War (1982 to date)

Till today, there is a lumber trade war between the United States and Canada. These two long-time trading friends are yet to settle their quarrel over wood imports and exports. Also known as the Softwood Lumber Dispute, it is one of the longest-lasting trade wars and involves a series of disagreements.

Hostilities began after key players in the United States lumber industry frowned at the Canadian government’s high subsidy on their softwood. They claimed the subsidies allowed the Canadian lumber companies an advantage over the United States and flooded its market with cheap wood.

The reason for this advantage is that most Canadian forests are owned by its government. These regional governments then charge Canadian lumber companies significantly lower fees than the United States for felling trees and selling timber. This resulted in Canadian timber becoming way cheaper than that from the U.S.

This much lower price gave Canadian timber an edge in the U.S. market. These complaints by the U.S lumber industry players led to a U.S. government-ordered inquiry in 1982. The investigation declared that the Canadian lumbar guys weren’t enjoying any unfair subsidies.

The issue came up again in 1986 when the United States government imposed tariffs on Canadian timber. This move forced the Canadians to the negotiation table, following which a deal was reached. In 1991, the same issue triggered court cases and further negotiations.

In 2001, the dispute escalated, leading to the U.S. slamming Canada with increased tariffs. Lastly, in 2016, following the expiration of a previous agreement, the U.S. angered Canada by imposing duties on its timber exports.

Even though the United States and Canada have continued to be great trading partners to date, the dispute over timber has raged on.

The Banana War (1993)

Bananas were the commodity of interest in 1993 when the European Union (EU) squared off against the United States and a number of Latin American countries. The problem started when the EU introduced a banana import policy that favored former European colonies and angered its Latin American exporters.

Banana exporters such as Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, plus some United States-based companies staged a protest against the move. The U.S. companies argued that the EU’s new regulations were unfair and violated global trade practices.

The U.S. led the fight, registering its displeasure with the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1996. After the investigation, the WTO sided with the complainants. However, the EU refused to reverse its course. It only made slight alterations.

Angered by the EU’s stubbornness, the U.S. slapped the union with reciprocal tariffs to the tune of $191 million. It took several interventions from the WTO before the war ended in 2012.

America and Europe Fight Over Steel (2002)

In March 2002, President George W. Bush signed off on a new tariff regime on steel imports. The tariffs, which were to last for 3 years, were levied on steel exporters ranging from 8% to 30%. His aim was to protect the dwindling jobs in the U.S. steel industry.

Most affected were countries in Europe, Asia, and South America. Some of them filed complaints with the WTO. At the same time, the EU also threatened to retaliate. Following the ruling of the WTO, which deemed the tariffs unfair and illegal, President Bush lifted the tariffs.

Trump Trade War (2018)

During President Trump’s first term, he imposed 25% tariffs on China’s steel and 10% on its aluminium. This came after he repeatedly complained about what he believed were China’s unfair trade practices.

He accused the Asian giant of stealing American ideas and intellectual property. He also stated that China had been taking advantage of the United States’ liberality to accumulate massive trade surpluses.

In July 2018, Trump followed up his early tariffs with another round. This time, he targeted other Chinese goods. He ended up raising tariffs to 25% for goods worth about $34 billion. This spurred China to fight back with it’s own tariffs.

But the U.S wasn’t done yet. Trump further increased the tariffs to affect about $360 billion in Chinese importable goods. China’s tariffs affected about $110 billion of U.S. exports.

The 2025 tariffs are a continuation of Donald Trump’s goal of leveling the playing field with China. He has called on the Chinese government to come to the negotiating table while trying to pacify U.S. consumers.

Truth be told, it is the consumers who bear the brunt of these tariffs. Higher tariffs simply translate to higher costs until the country can boost local production of the goods or both countries reach a compromise. Until then, the tit-for-tat continues, and import levies will continue to rise.