In the 1840s, thousands of mothers watched their children die in their arms. The whole nation was helpless. These were the years of Ireland’s Great Hunger.

Family members dropped dead one after the other due to starvation. Decaying corpses littered the streets. People were too hungry to dig graves. Many others fled for their lives. Desperate for survival, thousands crowded into “coffin ships” headed for America, where food was available. But only a few of them made it alive.

This is the story of how an avoidable famine ended millions of lives. It all happened under the callous eyes of British colonial masters. This dark episode serves as a chilling reminder of what can happen when people prioritize money over human lives.

To date, the 1840s Ireland famine remains one of the most painful and devastating episodes in human history. One that humanity must continue to learn from.

Ireland Before Disaster Struck

A few weeks before calamity invaded its streets, Ireland was a prosperous nation. There was food in abundance. Grains, livestock, butter, and potatoes poured out of numerous farmlands.

But there was one problem. Most of the food was for people outside the country—the real owners of Irish land: The British.

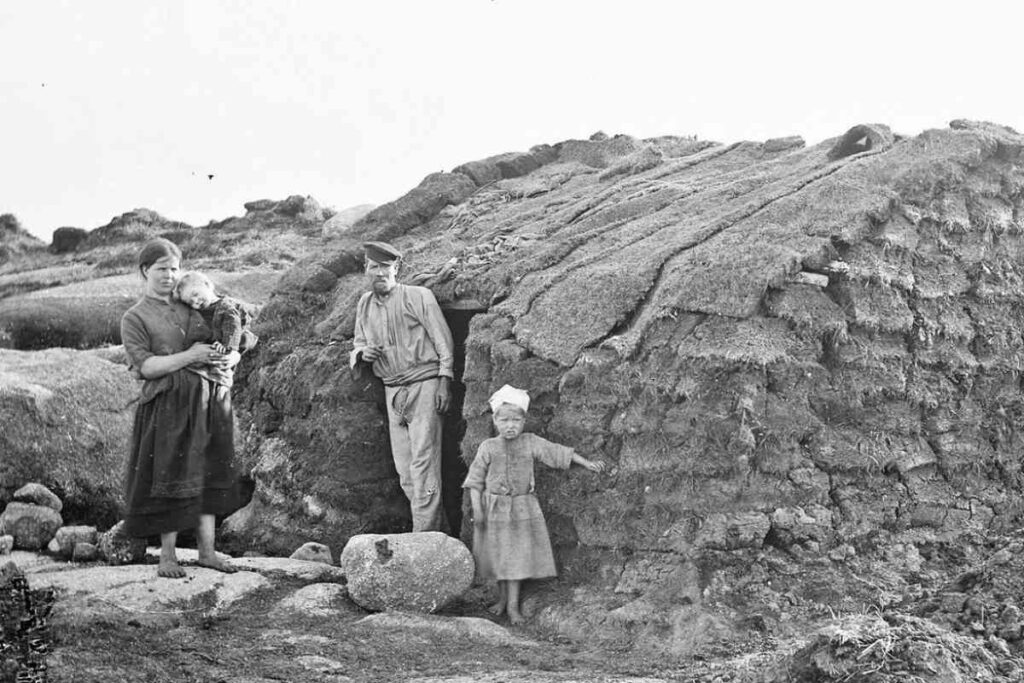

Ireland was under colonial rule. Therefore, its hardworking farmers were victims of colonial capitalism. This meant that Irish farmers were tenants on their own land.

A strange fungus, Phytophthora infestans, invaded European farmlands, targeting potato crops.

They toiled in the rain and sun to produce food for the landlords. Every day, vessels departed the nation’s coast to deliver food to British households.

The grains, livestock, and butter were for the British, while the potatoes were for Irish kitchens and dining tables. The farmers only had access to small portions of the farmland.

To get the most out of these little farms, every inch of them was used to grow potatoes. The starchy vegetables are rich in calories and vitamins. They could fill their stomachs and nourish their bodies simultaneously.

At the dawn of the 1840s, potatoes featured in almost every Irish dish. Nearly half of the country’s population feasts on potatoes every day.

Thereafter, tragedy struck!

The Blight Arrives

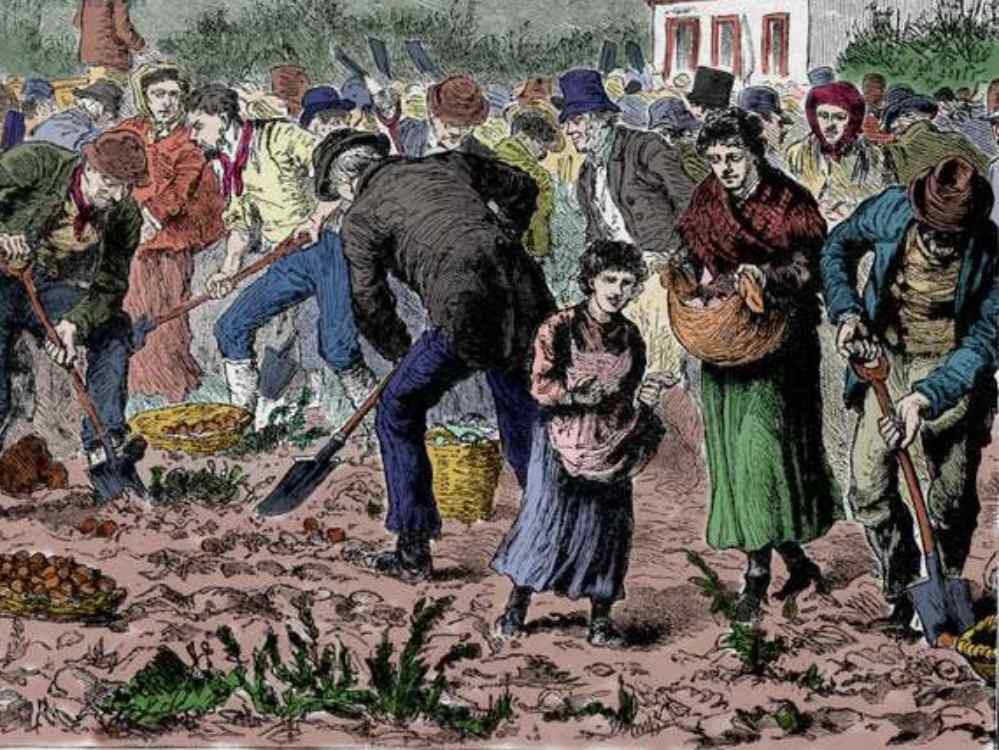

In 1845, Irish potato pits were empty. A strange fungus, Phytophthora infestans, invaded European farmlands, targeting potato crops.

Ireland was the most affected. The whole nation relied on potatoes for its survival. All of a sudden, they could no longer grow. The fallout was catastrophic. A massive wave of hunger spread through the land. It was a nationwide crisis.

Ireland was dying under extreme starvation, yet its food filled the bellies of outsiders.

By the winter of 1846, the signs of starvation were all over the land. Utterly helpless, families boiled weeds and chewed raw turnips. Then came the diseases. Cholera, dysentery, and fever struck with ease in the weakened bodies.

Throughout the day, children screamed from intense hunger. Hundreds of thousands turned to street begging. The whole nation was on the brink of extinction.

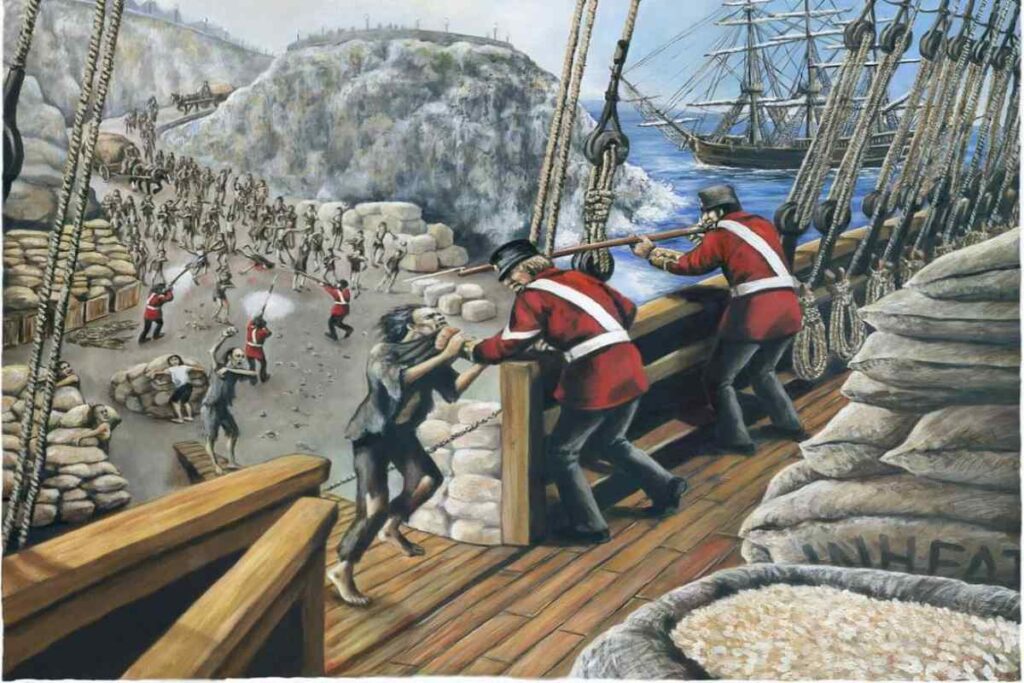

Yet, the exports never stopped.

In Cork, Limerick, and Dublin, ships were loaded with wheat, oats, barley, and livestock. These products of Irish soil were bound for Britain—their usual destination.

Ireland was dying under extreme starvation, yet its food filled the bellies of outsiders. But why? The answer is unbelievable.

Exporting Food and Importing Coffins

The British landowners valued profit over human lives.

Ireland played a crucial role in Britain’s economic success. It was the backbone of the British free-market system. British landowners rented lands to the Irish residents purely for profit. None of it was to feed the farmers.

The merchants were also under strict instructions. All the food must be shipped to Britain, where the landlords will profit more from higher prices.

So, even during the famine, business continued. There was no law stopping food exports during the famine. The landowners had their plans, and the starving Irish people weren’t part of it.

The then-British Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, and his successor, Lord John Russell, had the power to stop the madness. But tampering with the economy would create a problem that could harm their political careers.

Some British politicians advocated for the exports to cease and for food to be given to the Irish. However, they were overruled by their colleagues who were in the majority.

Back in Ireland, the people continued to suffer. The failing farms meant that people were no longer able to make a living.

Households sold their property and anything they could sell for scraps. As one writer would put it about a century later, “Ireland is exporting food and importing coffins.”

Bureaucracy as a Weapon

British colonial policy dashed Irish hopes. The colonial masters presented the matter to the British people in a weird way.

A test of morality and industry. That’s what the authorities in Britain told citizens.

The British government attributed the famine to natural causes in an attempt to downplay the role of exports in addressing the problem. Colonial authorities also blamed the Irish dependence on potatoes and overpopulation for the food crisis.

Between 1845 and 1852, more than a million people died due to the crisis. This was nearly one-eighth of the population.

They stated that the Irish famine would correct itself if the Irish people stopped being lazy. God was punishing them for their laziness and wiping them off the face of the earth to purge excess global population.

This and much more made up the elaborate propaganda they sold to their people.

When they finally sent relief, it came with conditions: Irish people had to work to receive help.

Starving men had to join in the construction of useless roads in exchange for little pay. The income from these efforts was still insufficient to cover the cost of most of the exported food.

The British opened workhouses for the starving population. These institutions soon filled to the brim and became death traps.

A Human Toll

The condition in Ireland continued to worsen as the years rolled past. Between 1845 and 1852, more than a million people died due to the crisis. This was nearly one-eighth of the population.

Whole Irish villages were wiped off not because there was no food, but because the British prioritized their market over humanity.

Those who tried to flee to America on ships died from the diseases that began to spread on board. The ones that made it were psychologically traumatized for the rest of their lives. They would never forget Ireland 1847.

Resistance and Memory

Ireland produced some strong opposition to the Irish farming exports. Several voices, ranging from the clergy to nationalists, rebuked the British for their conduct.

Interestingly, the Great Hunger has some benefits. Majorly, it increased Irish resentment against the British.

The anger over this great injustice in history grew into calls for independence. As the Irish people fled their country, they amplified the stories of the starvation in their new locations.

This mounted more pressure on the British to end their colonial control. The episode is one of the starkest reminders about the ugly side of colonialism. Colonial masters across the world were known to value other things above human life and the well-being of their subjects.

By the time Ireland gained independence in the 20th century, this hunger crisis was one of the reasons. It wasn’t just a natural disaster. It was a man-made situation.

Whole Irish villages were wiped off not because there was no food, but because the British prioritized their market over humanity.

This is a significant lesson for the rest of the world. No time should come when policy implementation takes precedence over welfare. Man wasn’t made for profit; profit was and should be made for man.

Some would think that the Irish people deserve some form of compensation for the unfortunate past. Do you agree?