History is full of betrayals!

Julius Caesar had Brutus, who struck him down in the Roman Senate. Napoleon had generals who deserted him when his empire began to crumble. Alexander the Great faced plots from his own trusted officers.

The Byzantine Emperor Maurice was overthrown by his own soldiers, the men he had once led into battle. Even in modern times, Fidel Castro’s closest ally, Camilo Cienfuegos, mysteriously disappeared; an occurrence that sparked whispers of betrayal in revolutionary Cuba.

And Chile? Well, Chile had Augusto Pinochet, the man who was trusted to protect democracy but who instead burned the palace and seized power.

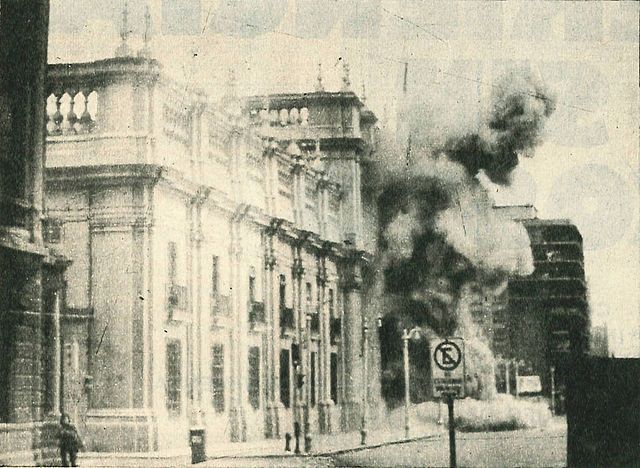

On the morning of September 11, 1973, Santiago, Chile’s capital, woke up to a sound that would echo through history. Fighter jets were screaming all over the city. It was not for an air show or for national pride. These jets carried bombs that were meant for the heart of Chile’s democracy: La Moneda Palace, the seat of government.

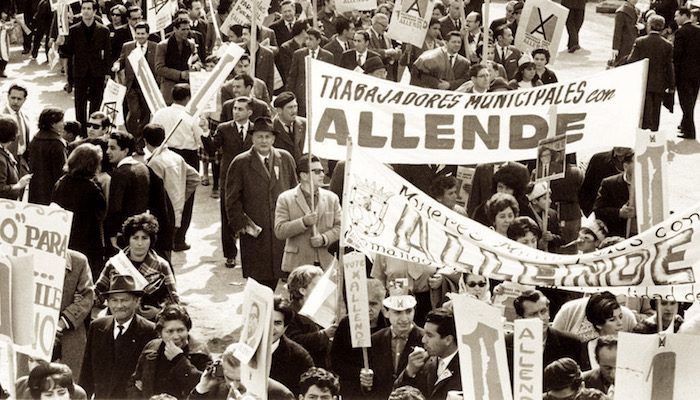

Inside the palace, President Salvador Allende sat with his closest allies. The Marxist doctor had been elected just three years earlier. He sought to address Chile’s profound social inequalities. He had promised land for the poor, milk for every child, and dignity for workers.

But the very moment when he knew he was surrounded by military tanks and under skies filled with smoke, he knew his presidency was about to end in flames. The man leading this attack was General Augusto Pinochet, whom Allende himself had trusted.

The world watched in shock as Pinochet led a military takeover that bombed the presidential palace, and a democratic reign. He turned Chile into one of the most feared authoritarian regimes in modern coup history. But this wasn’t just another Cold War coup. This was a story of trust that was turned into a weapon of destruction.

It is the story of a president who dreamed of a peaceful path to socialism, and of a general who wore loyalty on his uniform while secretly sharpening his knives. So grab a chair, because we are about to step into the smoke-filled streets of Santiago and see how the “loyal general” became the man who burned the palace.

Chile Before the Storm

To understand the 1973 Chilean coup, it is helpful to picture Chile in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Chile wasn’t a banana republic. It had one of the longest-running democracies in Latin America. Their elections were real, and presidents came and went peacefully. People debated politics with passion, sometimes too much of it, but the institutions were in place.

He wasn’t Stalin with a mustache, nor was he Mao with his little red books; he simply believed that you could create a socialist society through democracy, not dictatorship.

Then Salvador Allende came. A leftist politician who had been running for president for years but eventually won in 1970. His victory shocked the world because in the middle of the Cold War, when the US and the Soviet Union were fighting for influence, Chile had just elected a Marxist president without a revolution. There was no guerrilla war, no bloody uprising, just ballots.

Allende wanted what he called the “Chilean road to socialism.” He wasn’t Stalin with a mustache, nor was he Mao with his little red books; he simply believed that you could create a socialist society through democracy, not dictatorship.

So what did he do?

- He nationalized copper mines, many of which were owned by American companies.

- He gave land to poor farmers.

- He froze food prices so that workers could afford more.

- He raised wages.

To his supporters, he was a hero. He was “el compañero presidente” (the comrade president). To his enemies, especially in Washington, he was a red flag waving in their backyard.

The World Is Watching

This is where things get spicy.

Across the hemisphere, the US was obsessed with stopping communism. To them, Allende’s Chile looked like a potential second Cuba. And remember, Cuba was just a short flight from Florida.

Strikes paralyzed transportation, store shelves emptied, inflation ran wild, middle-class housewives banged pots and pans in the streets, demanding food, and truck drivers went on strike so often that the country seemed frozen.

The CIA didn’t sit still. Declassified documents later revealed that President Richard Nixon ordered his team to “make the Chilean economy scream.” The CIA funded opposition groups, strikes, and supported newspapers that painted Allende as a disaster.

The US was not the only one watching; the Soviet Union watched too. Although they supported Allende, they offered only limited economic assistance.

Within Chile, the economy was in decline. Strikes paralyzed transportation, store shelves emptied, inflation ran wild, middle-class housewives banged pots and pans in the streets, demanding food, and truck drivers went on strike so often that the country seemed frozen.

By 1973, the tension had become unbearable, and Allende, already desperate, turned to the military to maintain order.

Pinochet — The Loyal Soldier

Here is the twist.

Allende thought he had a secret weapon: the Chilean military. Chile’s army was seen as professional and disciplined, unlike many Latin American armies, which were prone to coups. And at the top of the military was General Augusto Pinochet.

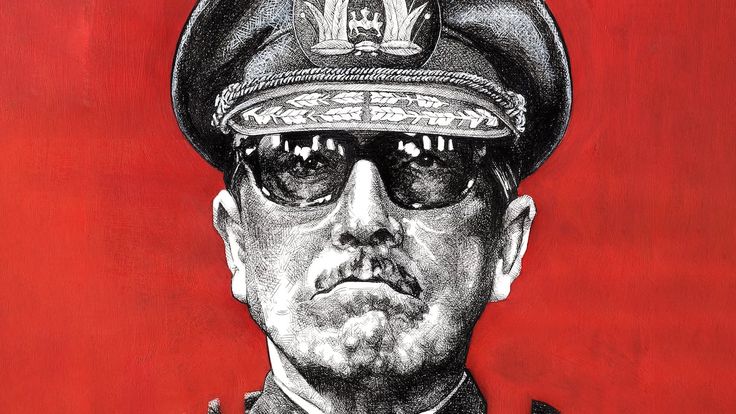

Pinochet was not a flashy man. He was a quiet, bookish man with thick glasses and a love for military manuals. To outsiders, he seemed boring; the kind of guy who would rather read about Napoleon than start a revolution.

When Allende appointed him as Commander-in-Chief of the Army in August 1973, he believed Pinochet would be loyal. After all, Pinochet had never openly criticized the government. He wasn’t loud, he wasn’t radical, he wasn’t plotting in smoke-filled rooms.

Or so it seemed.

Behind the scenes, Pinochet was already aligning with generals who believed Allende had to go. Once he was given command of the army, he had the perfect position to act.

The Day Democracy Burned

The coup began at dawn. Soldiers occupied radio stations, tanks rolled through Santiago, and navy ships took control of ports.

At 9 a.m., Allende gave his final radio speech. His words were calm but heavy. He refused to sign, saying he would pay with his life if necessary. He told Chileans that history would judge those who betrayed the people.

By mid-morning, Pinochet’s forces surrounded La Moneda Palace. At 11 a.m., fighter jets bombed the building, and flames with smoke rose over Santiago’s skyline.

Inside the palace, Allende fought back with an AK-47, which was a gift from Fidel Castro. But he knew it was over. Around 1:30 PM, the president had died. Officially, it was said that he committed suicide, but many Chileans believe he was killed by soldiers. However, one thing is clear: the era of democracy had ended in fire.

Fear Becomes Policy

Pinochet wasted no time at all. By evening, the military junta announced that it was taking over, and Allende’s supporters were hunted down.

The man who had once been quiet and obedient now ruled Chile with an iron fist.

Chile’s national stadium was turned into a mass prison camp. Thousands of people, including students, union leaders, and musicians were all locked inside. Some were executed, others tortured, and many disappeared.

One of the most famous victims was Victor Jara, a folk singer, who was loved by the people. Soldiers broke his hands so that he would never be able to play guitar again, then shot him. His death became a symbol of Chile’s broken soul.

Pinochet himself became the face of the new regime. The man who had once been quiet and obedient now ruled Chile with an iron fist. His dictatorship would last 17 long years.

The Dictatorship That Changed Chile

Under Pinochet, Chile became a laboratory for a new kind of dictatorship.

Unlike old-school generals who only cared about military power, Pinochet invited a group of Chilean economists who were trained at the University of Chicago. They were nicknamed the “Chicago Boys.” They pushed radical free-market reforms, including privatization, open markets, and cutting social programs.

Chile’s economy eventually stabilized and grew, but it did so at a heavy price. Poverty skyrocketed in the 1970s and early ’80s, and inequality deepened. Meanwhile, politically, Pinochet ruled through fear.

Censorship silenced critics, and secret police hunted down those who spoke out against Pinochet’s policy. More than 3,000 people were killed or disappeared during his reign, and tens of thousands were tortured.

Internationally, Pinochet was both hated and admired. To the US government, especially under Nixon and later Reagan, he was a useful ally against communism. To human rights activists, he was one of the world’s most brutal dictators.

The Fall of the General

By the late 1980s, Chileans were tired of fear, and protests grew. The economy improved, but freedom remained suppressed.

It was a rare moment in Cold War history; a dictator was forced out by the ballot box.

In 1988, Pinochet held a plebiscite, which is a yes/no vote, on whether he should stay in power. He was confident that he would win, but to his shock, the people voted “No.”

It was a rare moment in Cold War history; a dictator was forced out by the ballot box. Pinochet stepped down in 1990, but he ensured his protection. He remained head of the army for years and later became a senator for life.

Justice came slowly. In the 1990s and 2000s, Chile tried to prosecute him for human rights abuses, but Pinochet always managed to slip away, citing poor health as an excuse. He died in 2006 without ever serving a day in prison.

The Legacy of Fire and Fear

The coup that happened in Chile in 1973 remains one of the most dramatic examples of how fragile democracy can be.

Think about it. Allende trusted Pinochet. He believed the military would defend democracy, but instead, that trust became the weapon that destroyed it.

It illustrates how quickly democracy can crumble when fear supplants trust, how a loyal general can turn into a traitor overnight, and how, during the Cold War, small nations often become battlegrounds for superpower maneuvering.

For Chileans, the scars remain. Families still search for loved ones who disappeared, and streets and monuments carry the names of the victims. Every September 11, Chile remembers its own 9/11, not of foreign terrorists, but of their own army turning its guns on its people, betraying their oath.

It is a day of mourning and reflection; a reminder of how fast democracy can fall and how heavy the price of betrayal can be. Even decades later, the echo of fighter jets over Santiago still lingers in Chile’s memory, like a wound that refuses to heal.

The Chile 1973 coup is not just a story about one country; it is a warning. It illustrates how quickly democracy can crumble when fear supplants trust, how a loyal general can turn into a traitor overnight, and how, during the Cold War, small nations often become battlegrounds for superpower maneuvering.

Allende dreamed of democracy and socialism walking hand in hand. Pinochet dreamed of order and control, regardless of the costs. In the end, Chile paid in blood, silence, and scars that are yet to fully heal.

In Conclusion

Augusto Pinochet was appointed to protect Chile’s democracy, but instead, he destroyed it. Allende died with his boots on, refusing to abandon the palace. Pinochet lived long enough to see himself called both a savior and a monster. The coup that changed Chile wasn’t just about politics; it was about betrayal, fear, and how dangerously fragile trust can be.

And maybe that is why this story still matters today, because somewhere in the world right now, another “loyal general” may be standing beside a president, waiting, smiling, and sharpening his knives.

History like this still sparks debate: was Pinochet a savior, a tyrant, or both? What do you think? Drop your thoughts in the comments, and share this with someone who loves history as much as you do.