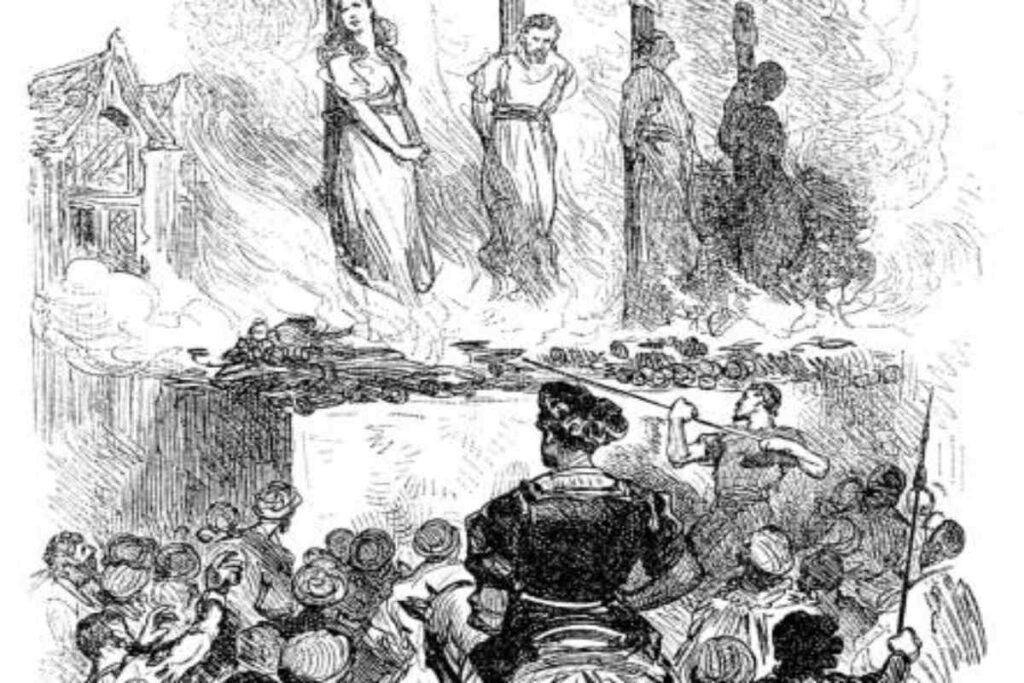

In December 1022, the French city of Orléans witnessed a horrific event. 13 persons, mostly Catholic priests, were tied to stakes and burned to death.

It was the first heretic burning ever witnessed in Christian-dominated Western Europe. It triggered a series of similar events that marred church history. Their only crime? Heresy.

The shocking execution followed a public trial. The highest-ranking members of the French royal family grilled the men. They found them guilty and declared death as their punishment.

Although it wasn’t the first time they had found people guilty of heresy, none of the other convicted persons were condemned to die. The usual punishment was exile, public shaming, or imprisonment.

The incident sent chills down the minds of the highly religious population. The crowd watched as the flames moved destructively throughout the flesh of the men, spreading agony through their hearts.

This death penalty was not just brutal and merciless, but it was a trigger. It opened the door for many more medieval heresy trials and executions by fire.

By the beginning of the 11th century, some subtle shifts had already begun. Defiant voices started to rise, calling for reform within the Church.

This case led other tribunals to view heresy as a crime punishable by death. As a result, hundreds more people across history were sentenced to be burned at the stake.

The fire that consumed their bodies continued to burn for many more centuries. The 1022 Orléans heresy trial introduced a culture of religious violence, from the Inquisition to the early witch hunts.

It opened a brutal dimension in history that should never have been. But it exposed the deadly combination of religion, politics, and intolerance. This mixture became a shameful blot on church history.

The World of 1022: Faith, Power, and Fear

The Europe of 1022 was worlds apart from what we have now. Back then, the continent was virtually under the canopy of the Catholic Church.

Governments collaborated with and even bowed to the wishes of the papacy. For many rulers, their authority and legitimacy flowed partly from Rome.

The people lived under the unquestionable influence of the church. No one dared challenge its directives and doctrines. It was like warring against the structure of society itself.

However, by the beginning of the 11th century, some subtle shifts had already begun. Defiant voices started to rise, calling for reform within the Church. These calls interrupted the free-floating loyalty that the religious setup had always enjoyed from every generation.

People began to take a closer look at church systems. Suddenly, the Catholic Church was no longer as healthy as many people had previously thought. Independent thinking emerged.

The government and the church observed with dismay the new mental rebellion. How much longer before it would lead to actual rebellion and the rejection of the authority of priests, bishops, and even the Pope?

The fear of heresy became a big issue. A revolution was brewing. For the authorities, drastic action was necessary.

A Quiet Rebellion: The Orléans Circle

Interestingly, the Orléans heretics weren’t unlearned people. They were influential clergymen. Most were priests who had ties with the royal house.

These clerics weren’t far from the seat of power, even literally. They resided in a building close to the cathedral, where they lived disciplined and patterned lives.

They were accused of rejecting the Virgin Mary and the Saints, dismissing the Church’s authority to forgive sins, and denying the doctrine of resurrection.

The priests deliberately rejected affluence and comfort, choosing to live the simplest lives possible. They taught the people to follow suit. To live sacrificially and in holiness.

Everything seemed to go smoothly until word reached the royal family about the priest’s rebellion against the church leadership. According to reports later documented in church records, the clerics denounced core church doctrines.

They were accused of denying the sacraments: communion and water baptism. Reportedly, they taught that the rituals had no spiritual usefulness.

Also, they were accused of rejecting the Virgin Mary and the Saints, dismissing the Church’s authority to forgive sins, and denying the doctrine of resurrection.

To worsen matters, they reportedly held secret meetings. During these assemblies, they allegedly engaged in strange rituals and attempted to convert others into their fold privately.

These accusations could well have been exaggerated by their enemies. These men could have been innocent of the charges, as no serious evidence was presented during the trial.

However, authorities viewed them as threats to church and state power. Their trial made it evident.

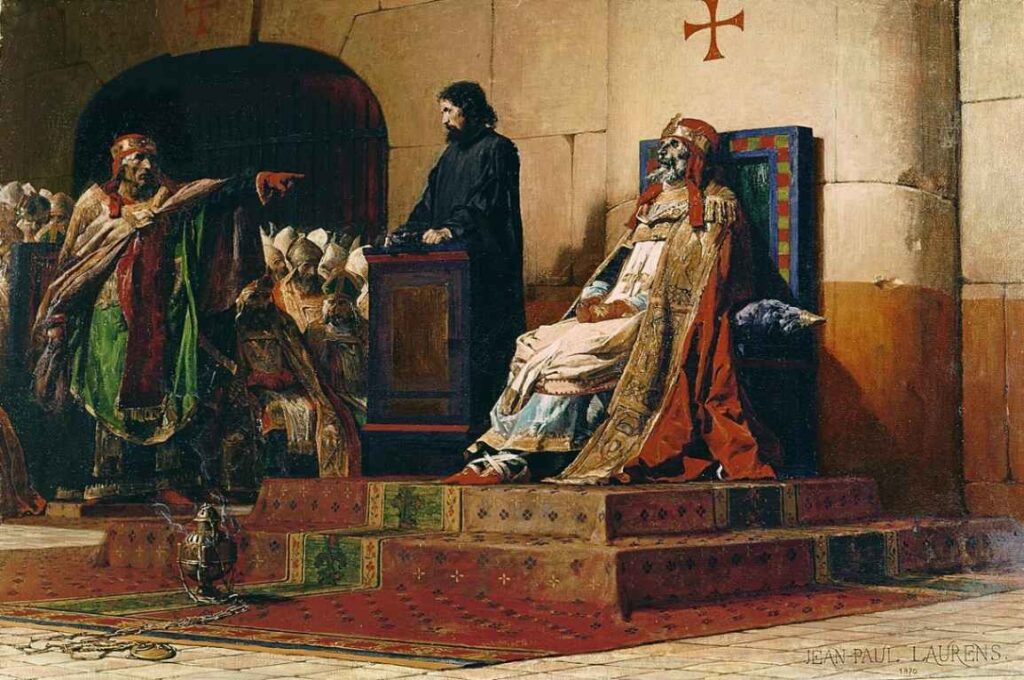

A Royal Court and a Public Trial

The 13 men stood before a panel supervised by King Robert II of France and his wife, Queen Constance. Most reports stated that while the king took a more lenient view of the offense, the queen insisted on the harshest of punishments. She used her influential voice to call for their deaths.

In an ample public space, the executioners lit a fire at the feet of the heretics. It was seen as a well-deserved punishment for the enemies of God.

Also, the populace was represented by an angry crowd. They filled up the trial grounds as word of the heresy charge spread through the land. The angry mob pushed for the priests to be dealt with.

As the tribunal questioned the suspects, it offered them a chance to renounce their strange beliefs and receive mercy. They declined the offer, choosing instead to face punishment.

They were probably not expecting anything beyond the usual. Their sentence, when it was finally read, took everyone by surprise.

Burned Alive: A New Kind of Punishment

For the first time, heresy was punished as a capital crime. But the people soon recovered from the shock. There were huge cheers as the men were dragged through the streets to the stake.

Then, in an ample public space, the executioners lit a fire at the feet of the heretics. It was seen as a well-deserved punishment for the enemies of God.

“Why fire?” many have wondered. Why not through numerous other means of death? The answer is grounded in spiritual mystery.

In such a religious setting, fire was a symbol of purification. The thinking was that it would purge the souls of the priests from evil. Ultimately, it would rid the world of rebellion against God.

After the Orléans heresy trial, public burnings began to pop up across Europe.

Another notable aspect of the execution was that it was done publicly. Public punishments were an effective way of instilling fear and control in medieval Europe.

It sent a message to other heretics or would-be heretics. No form of rebellion against the state will be tolerated. They will be met with brutal punishment.

This was the beginning of the practice of burning heretics in public. Future generations of leaders adopted the style. It became the glue that held church and state power together.

A Dangerous Legacy Begins

After the Orléans heresy trial, public burnings began to pop up across Europe. The church adopted the execution style to punish anyone who was found guilty of rebelling against its core doctrines.

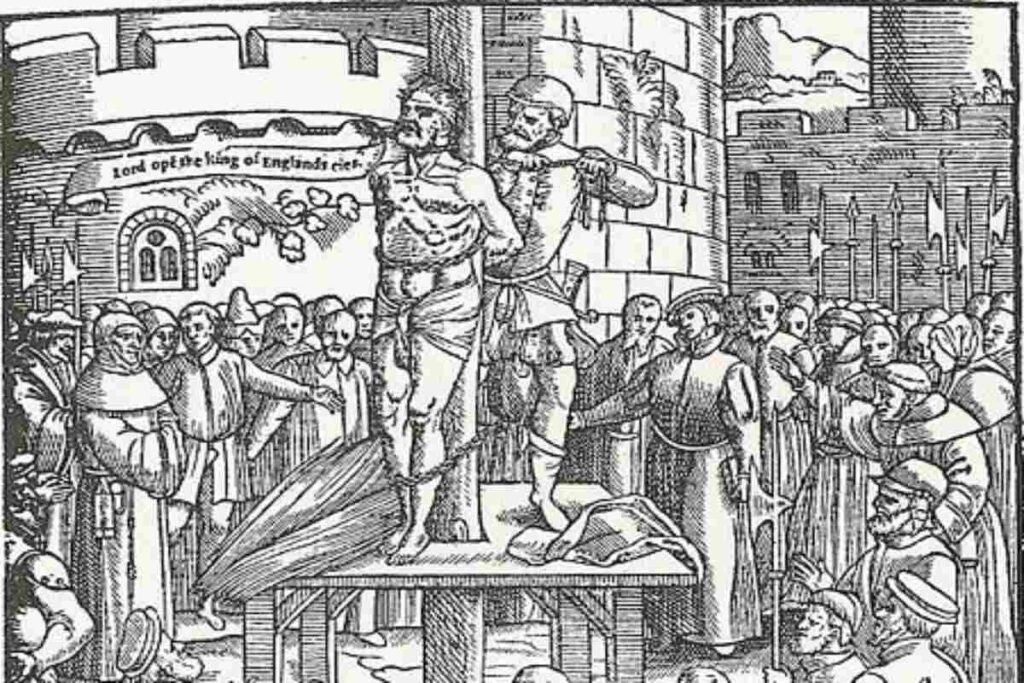

Parliaments began passing laws to legalize burning people at the stake. Then came the era of the Inquisition, a dreaded institution tasked with fishing out heretics and setting them ablaze in public.

The penalty was extended beyond heresy. Other forms of rebellion against church authority were punished by burning at the stake.

From Italy and England to Spain, crowds gathered to watch people with “wrong teachings” helplessly get roasted beyond recognition. Before and in addition to these brutal killings, the convicted persons were severely tortured.

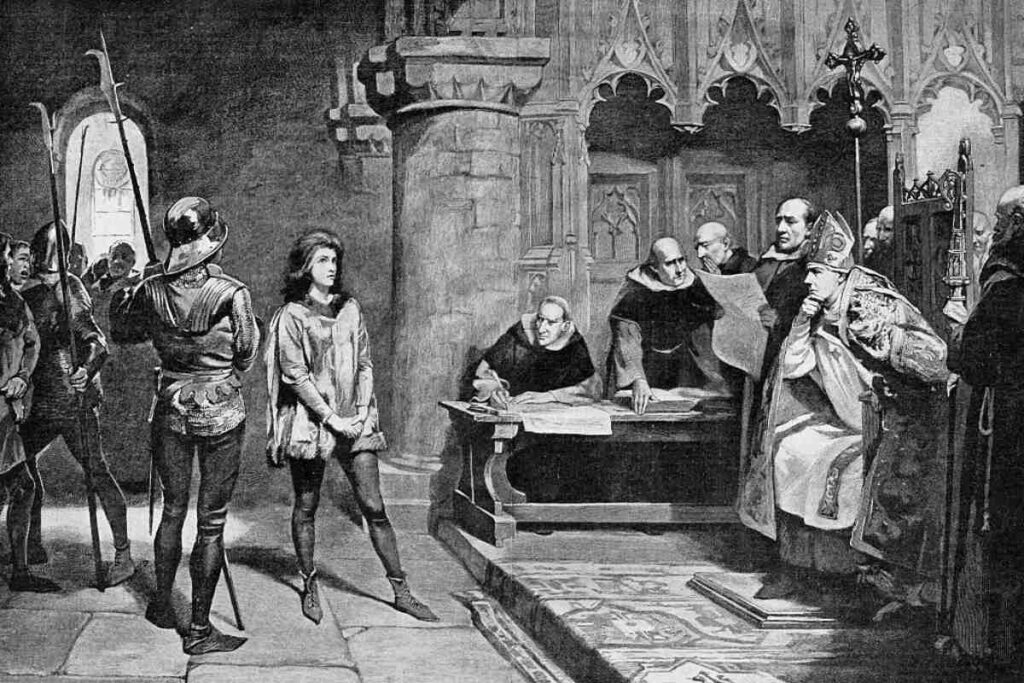

Notable people were convicted of heresy. Later on, the penalty was extended beyond heresy. Other forms of rebellion against church authority were punished by burning at the stake.

For example, William Tyndale, a popular Bible scholar, was strangled and burned in Belgium. His execution happened in 1536, and his crime was translating the Bible into English without the church’s permission.

Another was Michael Servetus, burned in 1553 in Spain for rejecting the doctrine of the Trinity and the practice of infant baptism. Joan Bocher of England died at the stake in 1550 for denying the doctrine that Jesus was born of a woman.

By the 15th century, the Inquisition had given rise to the Witch Hunts. Women who were believed to possess dark powers were targeted for execution.

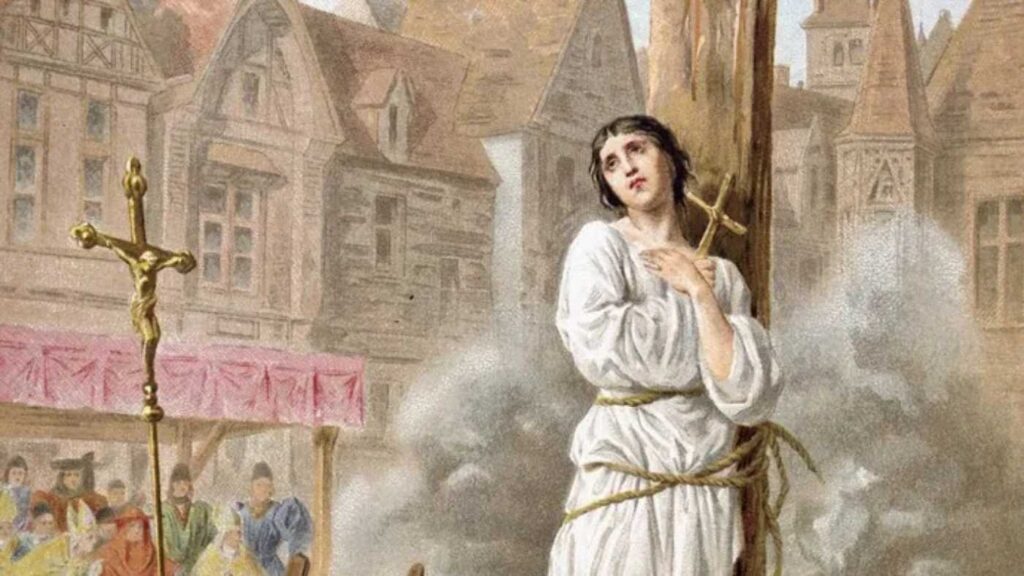

Joan of Arc was burned at the stake in 1431 in France. Merga Bien was roasted in Germany in 1603, amongst many others.

They never took a human life or robbed anyone. All they did was express their ability to think differently.

Belief as a Crime: The Real Danger

The heresy trials and killings opened a new page in medieval justice. It was previously unheard of that people would be punished, let alone eliminated, not for their actions but for their thoughts.

The practice has revealed how far justice has evolved across centuries. Now, we are free to practice any religion and even hold views that are outside the central doctrines of our faith.

Free speech is still being threatened in our day, especially on social media. In many parts of the world, oppressive governments still clamp down on opposing voices.

We are allowed to reason independently and even challenge popular opinions. This was a luxury back in the day.

But just like things changed drastically in ancient France, our freedoms can disappear with a snap of the fingers. The story of the 13 convicted Orléans citizens is a sobering reminder.

All it takes is an intolerant and jittery government, plus an angry population, and we could be back to the old era.

One Fire, Many Shadows

Although no one gets burned at the stake anymore, the flicker from the Orléans fire is still alive. There are still instances where people face punishment for expressing their opinions.

Free speech is still being threatened in our day, especially on social media. In many parts of the world, oppressive governments still clamp down on opposing voices.

We all have a part to play. First, to protect those whose voices are being silenced. Secondly, to ensure that we aren’t tools of political and religious intolerance.

We must remember that freedom of speech for one is freedom of speech for all. We must not forget that people paid the ultimate sacrifice for where we are today.

As we continue to fight for freedom of thought and expression, never forget that the Orléans 13 are rooting for you. What modern event do you think closely resembles the Orléans heresy trial?