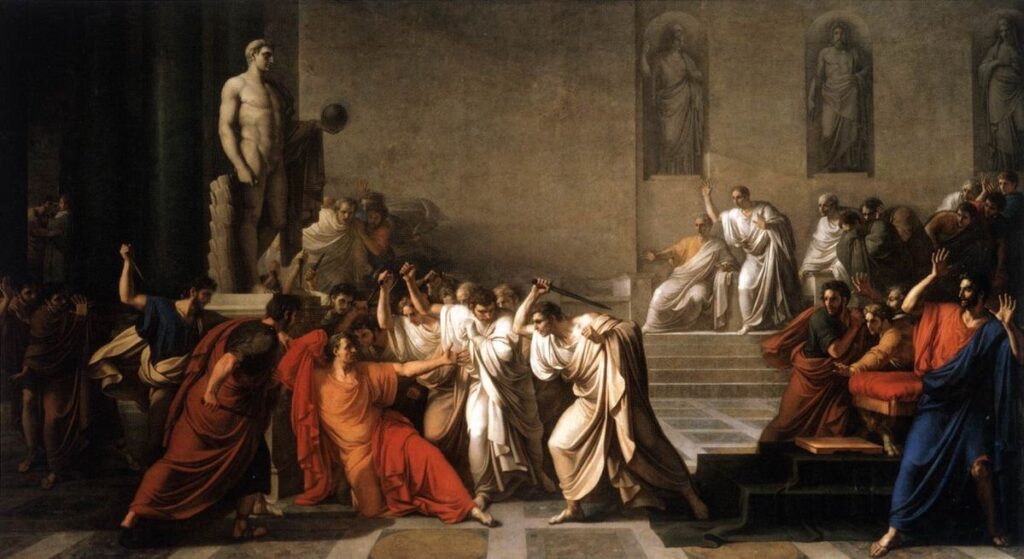

The Senate doors creaked open, and sunlight spilled across the marble floor. Inside the room, the most powerful man in the world, the conqueror of Gaul, master of Rome, and “dictator for life,” walked straight into the trap that was laid for him. The air was thick, not with the smell of water or the murmurs of crowds, no, not that. It was thick with the silent heartbeat of betrayal.

They were all there. Senators in their crisp ceremonial togas, their eyes fixed, hands trembling ever so slightly beneath the folds of cloth. Daggers waited in the shadows, and among them stood the one man Caesar would never suspect; the man he had trusted, promoted, and perhaps loved like a son.

History would remember his name as the symbol of treachery and betrayal. Rome would remember his act as the blow that ended the Republic, and the world would never forget the question that echoed through the ages:

How do you kill a father… and call it saving your country?

A Murder Written in History’s Boldest Ink

On the morning of March 15, 44 BC, Julius Caesar, the most powerful man in Rome, was getting ready to attend the Senate meeting. He was 55 years old, still sharp and energetic; a man who had conquered lands, outsmarted rivals, and had risen from a debt-ridden noble to a ruler of the known world.

However, this meeting will not end in debates and speeches. It would end in blood.

That day, the day known forever as the Ides of March, Caesar would walk into the Senate House and get stabbed 23 times by men he called his friends, allies, and in one case, almost a son.

That “son” was Marcus Junius Brutus.

The Twist in the Tale

Today, almost everyone knows the famous line: “Et tu, Brute?” (“You too, Brutus?”).

Whether or not Caesar actually said it is debated, but the meaning is clear. Caesar was not shocked that people wanted him dead. He was a politician in ancient Rome; he had enemies, and he was well aware of the fact.

What shocked Caesar was the person he saw holding the knife.

Romans had a thing against kings; they hated having them as rulers

Brutus wasn’t just another senator. He was the man Caesar had trusted and treated like a family member. Cesar had mentored him, trusted him, promoted him in politics, and, according to some rumors, perhaps even loved him like he was his own son.

So why? Why would Brutus drive a dagger into the heart of the man who made him?

To answer this question, we must step back into the chaos of Rome’s final days as a Republic.

Rome Before the Fall: Democracy… Kind Of

Rome during the time of Caesar and Brutus wasn’t a monarchy; at least it wasn’t officially. It was a Republic, with elected officials, powerful senators, and a political system that was designed to prevent one person from becoming king, regardless of who that person was.

Romans had a thing against kings; they hated having them as rulers. They had kicked the kings they once had centuries before, and built a government that was supposed to be ruled by law, not by one man’s will.

However, the problem was that by the first century BC, Rome’s political system was already in decline. Corruption was rampant; senators were more interested in personal power than in public service, and generals began using their armies for political leverage, not just for defense.

Caesar was one of these generals, but he was smarter, more charismatic, and he had far more ambition than the other generals.

The Rise of Caesar

Julius Caesar’s rise to the top was the stuff of legends. Although he came from a noble family, he grew up in poverty. He survived political purges by being clever and charming. Caesar quickly rose to the top of Roman politics while simultaneously becoming one of its greatest military commanders.

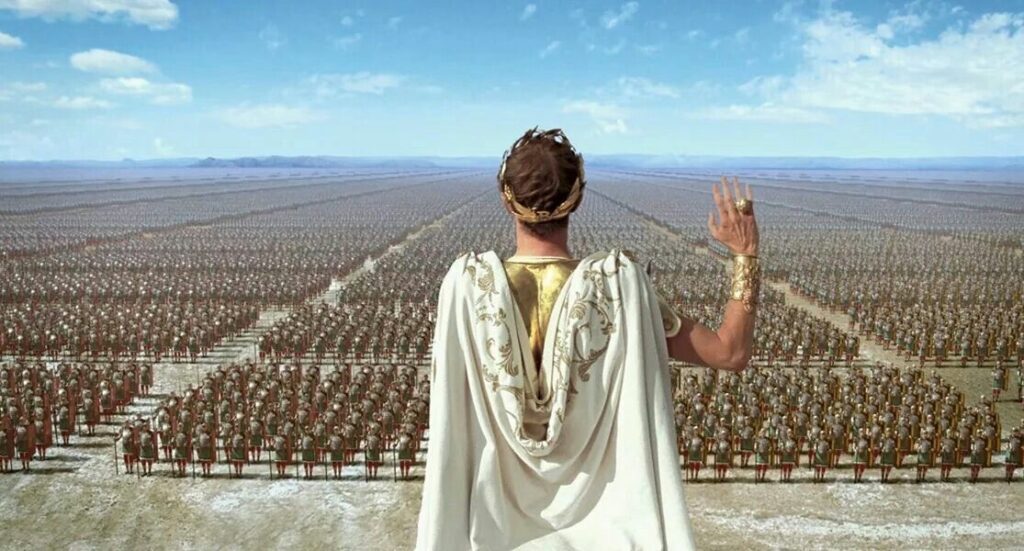

When he conquered Gaul, that is, modern-day France, it made him alarmingly rich and incredibly popular. But unsurprisingly, this feat also made the Senate nervous. Senators felt that way because a man with both wealth and a loyal army could easily become a dictator. So, they devised a plan. They would ask…no, they would order the man to give up his army.

Many senators believed that if Caesar stayed in power forever, the democracy in Rome, as flawed as it was, would be gone for good.

When the Senate ordered Julius Caesar to give up his army, he made a fateful choice. Instead of obeying them, he marched his troops across the Rubicon River into Italy in 49 BC, and guess what he did?

He started a civil war.

Back then, Caesar proved that he wasn’t just all talk because by the end of the war, he had emerged victorious. His rivals were either dead or in exile. He was now dictator for life.

And that was the problem.

Why Being “Dictator for Life” Was a Death Sentence

The title “dictator” in ancient Rome was not always a negative connotation. In times of emergency, the Senate would appoint someone as dictator for a period of six months to handle a crisis. But for life? That sounded way too much… It was like having a king.

The Senate’s pride, and the Republic itself, were at stake. Many senators believed that if Caesar stayed in power forever, the democracy in Rome, as flawed as it was, would be gone for good. One of those senators who thought this way was Marcus Junius Brutus.

Why Brutus Turned Against Caesar

Marcus Junius Brutus was not just any politician; his ancestors were legends in Roman history. One of them was Lucius Junius Brutus. Lucius had famously overthrown Rome’s last king centuries earlier, and he helped found the Republic.

That family legacy weighed heavily on Brutus. To him, protecting the Republic was not just politics; it was his destiny.

He had faced death on the battlefield countless times. Why should he fear a room full of politicians?

However, here is the twist: Brutus owed much of his career to Caesar. Caesar had forgiven him for taking sides with his enemies in earlier conflict, promoted him, and trusted him deeply. Caesar may have believed that his bond with Brutus was unbreakable, but to Brutus, the bigger loyalty was to Rome itself.

The Conspiracy Forms

By early 44 BC, whispers of a plot to kill Julius Caesar were already circulating the city.

The main leaders were men like Gaius Cassius Longinus, a fiery senator who hated Caesar, and Decimus Brutus, a trusted general (note that he has no relation to Marcus Brutus). They needed someone whose reputation would give the assassination a sense of honor, not just politics.

That someone was Brutus.

Cassius played on Brutus’s sense of duty. He reminded him of his ancestor who overthrew a tyrant. He painted Caesar as a threat to everything Rome stood for, and slowly but surely, Brutus was convinced.

The Ides of March

The Senate meeting was scheduled for the Theatre of Pompey, which was an odd choice, since it was a building that was tied to Caesar’s dead rival, Pompey the Great.

That morning, Caesar’s wife, Calpurnia, begged him not to go to the meeting. She had nightmares of his murder. His friends also warned him of danger, and a fortune teller famously told him, “Beware of the Ides of March.”

Cesar didn’t pay any attention to these warnings; he just laughed them off. He had faced death on the battlefield countless times, so why should he fear a room full of politicians?

The Murder

When Caesar got to the Theater of Pompey, the conspirators surrounded him under the pretense of discussing politics. One of them grabbed his toga, another struck the first blow, then chaos erupted.

Julius Caesar tried to fight back at first, but once he saw Brutus’s face among the attackers, something in him broke. Ancient writers say he either pulled his toga over his head or simply stopped resisting. However, twenty-three stabs later, the ruler of Rome was dead.

The Aftermath: Freedom or Chaos?

After the gruesome ordeal, the conspirators expected the people to cheer them as liberators. They imagined speeches, applause, and a return to noble republican values. But they were wrong.

Instead, Rome erupted in panic.

Caesar had been loved by the common people, despite being a dictator. He had given them land, jobs, and festivals. To them, Brutus and the others were not heroes; they were murderers.

Marc Antony, Caesar’s ally, delivered a speech during the funeral. This speech completely turned public opinion against the assassins. The crowd rioted and protested until Brutus and the others had to flee the city.

Why Brutus Thought He Was Right

It is easy to call Brutus a traitor, and many have, for 2,000 years, but Brutus did not see himself that way. In his mind, Caesar was destroying the Republic. To him, the Republic was worth more than anyone’s life, regardless of who the person is. Even if it meant killing a friend, or even a father figure, then so be it.

Brutus saw the assassination as a patriotic surgery, not murder. He saw it as removing a dangerous growth to save Rome. The tragedy is that killing Caesar didn’t work the way he thought it would.

The Death of the Republic

Killing Caesar did not restore the republic; in fact, it had the opposite effect, shattering it.

In the power vacuum, Caesar’s allies, Mark Antony and Octavian, who was Caesar’s adopted heir, went to war with the assassins. Brutus and Cassius were hunted down, and they eventually committed suicide after losing at the Battle of Philippi in 40 BC.

Then Octavian became Augustus, the first Roman emperor. The Republic that Brutus died to save was gone forever.

Power vs Loyalty: The Eternal Question

The story of Brutus and Caesar isn’t just ancient history; it is a question humans still face: When does loyalty to a person, and loyalty to a principle begin?

The betrayal was meant to stop an emperor, but it ended up crowning one.

Brutus chose the principle of republican government over a personal loyalty to Caesar. He thought he was saving Rome, but in reality, his choice was a catalyst for the very thing he feared: the birth of an empire ruled by one man.

It is one of history’s greatest ironies. The betrayal was meant to stop an emperor, but it ended up crowning one.

The assassination of Julius Caesar has everything. A larger-than-life leader, a shocking betrayal, political ideals clashing with personal loyalty, and the dramatic collapse of a centuries-old system.

It is a reminder that power is never just about laws and offices; it is about people, relationships, and trust. When that trust is broken, the consequences can be far greater than anyone intended it to be.

Conclusion: When Loyalty Cuts Deeper Than Any Dagger

On the Ides of March, Brutus stood over the bleeding body of the man who had been his mentor, benefactor, and father figure. In his hand was the dagger that had ended one life and, in a way, ended an entire era.

History remembers Brutus as both hero and villain. While some people regard him as a noble defender of liberty, others view him as the ultimate traitor.

However, one truth remains unshaken: in that moment, after Julius Caesar’s death, the future of Rome changed forever. The Republic’s death was not only written in blood, but it was also written in betrayal.

Perhaps that is why the story still resonates today, because it poses the question we are never quite ready to answer: Would you betray the one you love to save the world?

So now it’s your turn. If history put you in Brutus’s sandals, what would you have done? Drop your thoughts below, and if this tale gripped you, share it with someone who loves a good betrayal story.