If you lived in Cambodia in 1975, you would have joined the rest of the nation in wild celebration. The capital city of Phnom Penh came alive on April 17 to welcome Pol Pot, the leader of the famed revolutionary army called the Khmer Rouge.

The group had just won a brutal civil war and had taken control of the whole nation. Peace had finally returned after many months of terror.

The city of Phnom Penh was looking forward to a new Cambodia, free from the sufferings and misrule of the past. But they got something worse than they imagined.

Shortly after entering the city, the smiling combatants suddenly switched, unleashing terror on the jubilant population. The fighters went on a killing spree, drastically reduced the population, and turned the nation upside down.

They were implementing a plan they called “Year Zero,” a complete reorganization of history, culture, and society.

The Khmer Rouge was a militant group that emerged from among the people. It was founded on communist ideologies and had vowed to rebuild the Southeast Asian country.

After the massacre, they banned the use and possession of money, scattered families, shut down schools and hospitals, and emptied entire cities. They were implementing a plan they called “Year Zero,” a complete reorganization of history, culture, and society.

This ambition led to one of the most horrifying and, in many people’s opinions, forgotten genocides of the 20th century. It was a chilling episode in Asian history. One that many people prefer not to remember.

It was all for the fulfillment of one man’s fantasy. Pol Pot wanted to reset the nation and build it differently from the very beginning. But was this plan worth it?

The Ideology of Year Zero

The Khmer Rouge were implementing a radical plan. “Year Zero,” as the name implied, aimed to achieve a complete wipeout of society, to bring it back to zero, to the very beginning.

Some of the targets of this cleanup were religion, education, and capitalism. Other targets include the family setup and anything that resembles modern life.

The Khmer Rouge saw all these elements as fundamentally corrupt. They also believed that they had to demolish these structures of the past to build a new and just society.

Pol Pot wanted to rid the country of every symbol and trace of colonialism. He believes that economic inequality and moral failure in society were purely a product of Western influence.

Pol Pot built his plan on the foundation of the Chinese Cultural Revolution of Maoism. He saw a society built on the Marxist and Leninist principles of equal wealth distribution and agricultural boom.

But first, modern Cambodia had to give way for this perfect society to form. Pot and his army had to clear out entire cities in a brutal and never-before-seen fashion, which became known as “death marches.”

Evacuating the Cities: The Death Marches

To rebuild, the Khmer Rouge had to empty the cities. They would start from the capital, Phnom Penh, forcing over 2 million residents to vacate their homes and their beloved city.

Lawyers, doctors, engineers, teachers, religious leaders, business people, and students were marched out of the city at gunpoint. The militants didn’t spare the sick and elderly.

The new rulers told the former inhabitants that the relocation wouldn’t last for very long. After reconstruction, they would return to their land and homes.

But it was a lie. The residents of Phnom Penh were never going to see their city again.

Pol Pot wanted to conduct a thorough cleanup of everything that made Cambodia what it was.

During the death marches, several things happened. Many were unable to reach the new destination. They died on the way, mostly from starvation, exhaustion, and dehydration. The inpatient soldiers also killed many on the road.

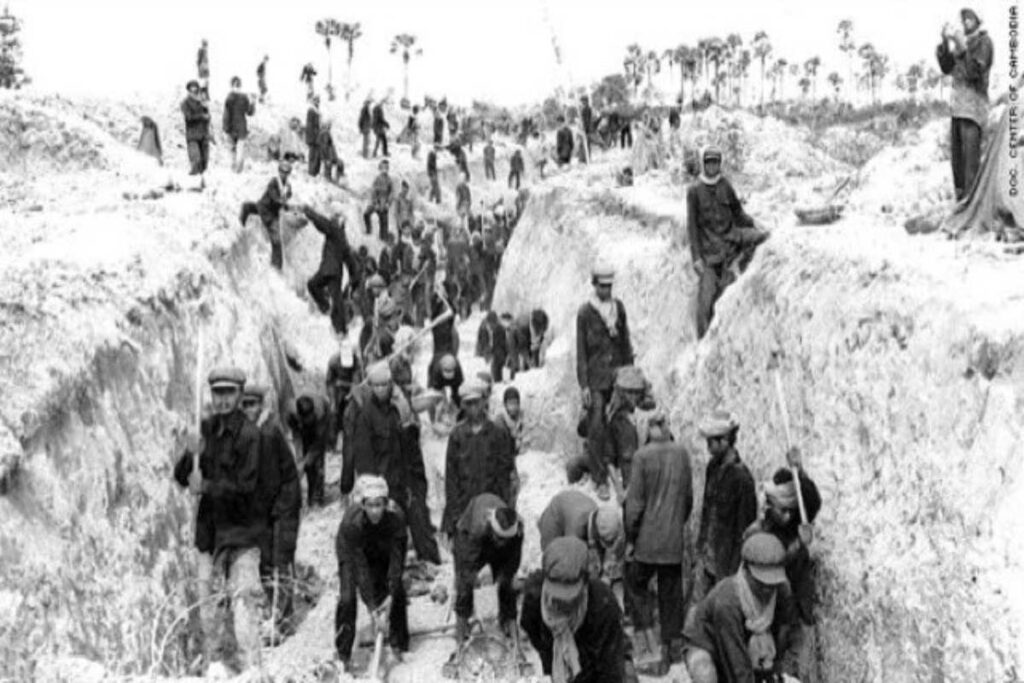

Those who made it were sent to labor camps. There, they were forced to work on the farms for many hours. They did these under terrible conditions.

They completed strenuous tasks without proper farm tools. They also lacked food, water, and a place to lay their heads.

The deserted cities were to be demolished, including Phnom Penh. They were all converted into massive rice fields.

The War on Culture and Identity

Aside from physical structures, culture was also a threat to the militants. They had it in mind to pull down Cambodia’s cultural heritage.

They specifically targeted religion, marriage, language, literature, art, music, and traditional dance. Pol Pot wanted to conduct a thorough cleanup of everything that made Cambodia what it was.

- Religion was outlawed. Buddhism, the nation’s dominant religion, suffered a significant setback. Many of its temples were destroyed and repurposed for agricultural purposes. Sacred places of worship soon became shelters for pigs. Others were used to house grains and other farm produce. The new government killed many Monks and religious leaders. The ones that survived were either stripped of their spiritual authority or banished from the land.

- Language and literature were also banned. The combatants invaded libraries and burned thousands of books. People were warned not to speak any foreign language. Also, it became unlawful to express any knowledge of the nation’s royal heritage or colonial history.

- Art, music, and traditional dance were branded as leisure activities for the rich. The new rulers took it upon themselves to clamp down on any trace of them. They smashed musical instruments and even killed some classical dancers. One by one, everything that made Phnom Penh what it was vanished into thin air.

- Marriage was heavily regulated by the revolutionary agents. The Khmer Rouge conducted mass weddings and interfered in family privacy. Children were snatched from their homes, indoctrinated, and sent back to spy on their families.

Radical Equality Through Mass Murder

Pol Pot and his gang weren’t done yet. To bridge the class gap, they proposed and implemented a horrific plan: social equality by mass execution.

The Khmer Rouge began to take out anyone who showed signs of elitism. Wearing glasses could attract the death penalty.

People got killed because they spoke foreign languages. Same as those who had soft hands. Yeah. Tender hands were regarded as a sign of affluence and worthy of death.

As a result, many parts of Cambodia became killing fields. After the Khmer Rouge reign, authorities found over 20,000 Cambodian mass graves.

At these sites, the Khmer Rouge beat citizens to death. They smashed babies against trees and threw lifeless bodies into pits.

In this facility alone, at least 17,000 people were tortured and killed. This included men, women, and children of all ages.

The new regime came down hard on any opposing voice or anyone who seemed likely to challenge their authority.

People in this category were either imprisoned or executed. The Khmer Rouge built a lot of prisons and torture houses. The most notable one was called S-21, also known as Tuol Sleng. This facility was once a school.

In this facility alone, at least 17,000 people were tortured and killed. This included men, women, and children of all ages. Many of them were forced to admit to ridiculous crimes such as being American spies.

The Khmer Rouge atrocities were unimaginable. So much so that when their evil reign finally ended in 1979, close to 2 million Cambodians had died. This was about a quarter of the population.

Their radical communism delivered what is referred to as the Cambodian genocide, one of the darkest chapters in Cambodian history. But Pol Pot wasn’t the only one making the decisions.

The Madness of Angkar

The story of the Year Zero Cambodia era wouldn’t be complete without the mention of the Angkar. Also referred to as “The Organization,” this body gave the go-ahead to the Pol Pot reset plan and the Cambodian war crimes.

The group consisted of senior members of the Pol Pot regime whose identities remained a mystery. This level of secrecy was intentional. This strategy aimed to put the population in perpetual fear and dread of the Angkar.

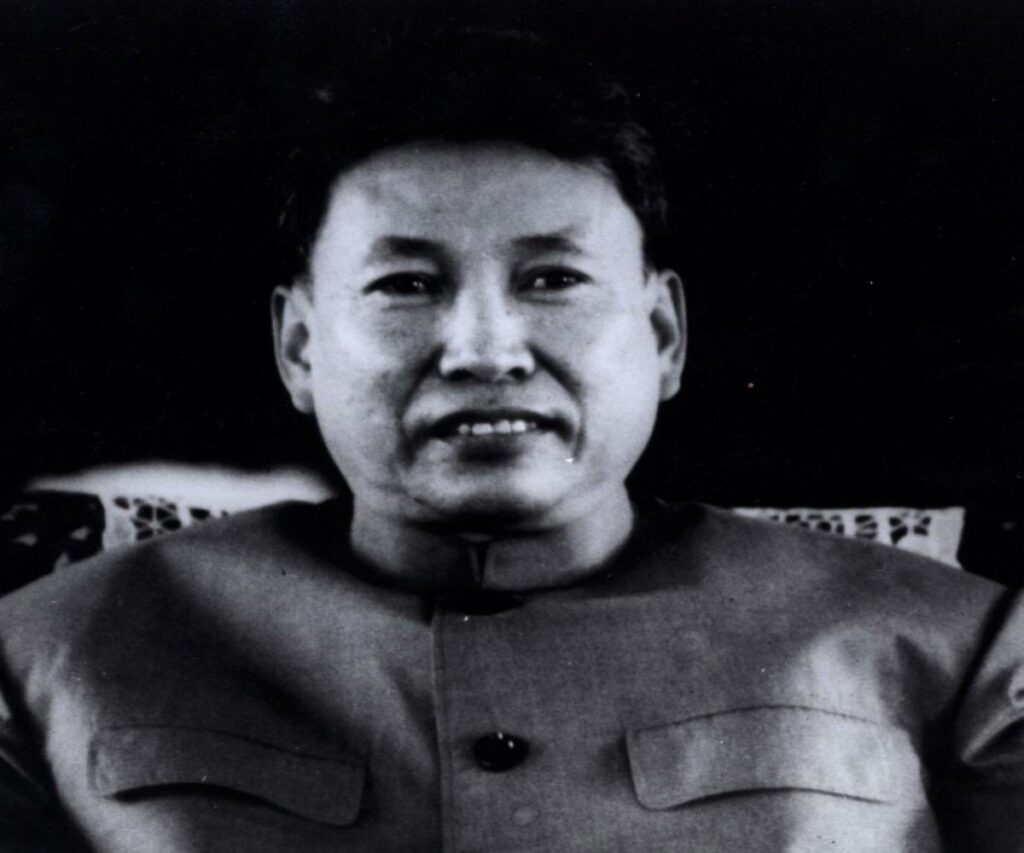

Pol Pot himself was hardly seen. He stayed in the background, and much of his life and activities were covered in mystery. However, we know a bit about the man.

Pol Pot’s actual name was Saloth Sar. He was born into a wealthy family in 1925 and received his education in France in the 1950s.

It was during this time that he came in contact with communist groups. These associations produced dangerous ideas about how society should run.

With the support of the West, he lived quite comfortably. But the nation he ruined struggled to get back on its feet.

Following his return to Cambodia, Pot joined the Khmer Rouge. At the time, it was a secret communist movement. As a result of his passion, courage, and leadership skills, he climbed up the ladder to eventually head the group. Pol Pot was a die-hard believer in the movement.

His dedication to his communist ideals was tested after he was overthrown by Vietnamese soldiers in 1979. But he never gave up his beliefs.

After he was removed from power, he ran into hiding deep in the northern Cambodian jungle. There, he maintained leadership of the few men left of the Khmer Rouge.

Later on, with the support of the West, he lived quite comfortably. But the nation he ruined struggled to get back on its feet.

It was in 1997 that his life finally came to an end. His soldiers became disloyal. They arrested him and detained him in his house. He died the following year, shortly before he was to be transferred to international authorities to answer for his misdeeds.

Pol Pot’s life didn’t end the way many would have wanted. Instead of answering for his crimes against humanity, he died before he could face punishment. His victims weren’t as lucky.

The Aftermath: Trauma and Memory

Many survivors of the Pol Pot era never fully recovered from the dark event. The scars of the Year Zero movement endured for many decades.

The Pol Pot crimes destroyed families and wiped out entire generations. Those who scaled through had to live the rest of their lives with the horrible memories.

In 2003, the global community attempted to provide assistance. The United Nations collaborated with the Cambodian government to provide justice for the Cambodian people.

They established the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). This panel, also called the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, succeeded in convicting top leaders of the Angkar.

It is an example of how deadly one man’s fantasies can be to the lives of everyone around him.

But the tribunal has moved slowly. Many more suspects have had their trials delayed or abandoned. This unfinished project has complicated the pain of the traumatized victims.

The impacts of the Khmer Rouge atrocities remain visible to date. The events surrounding the fall of Phnom Penh set the country back by many years.

Today, Cambodia’s economy and educational sector are still recovering from the effects. The government has had to rebuild scores of schools, hospitals, and other facilities.

The nation continues to struggle with massive corruption and poverty. Additionally, it has yet to revive its culture and heritage fully.

Conclusion: Lessons From a Deleted Nation

The story of Pol Pot, one of the most deadly Southeast Asian dictators, has a lot to teach us. It is an example of how deadly one man’s fantasies can be to the lives of everyone around him.

In the case of Pol Pot, his utopian desires led to the destruction of a whole nation and one of the most brutal genocides in Asia.

In a bid to make Cambodia a better place, he destroyed the people who should have benefited from this plan. But more than that, he tried to erase the traces of their existence.

He waged war against their memory and culture. This is the frightening story of Year Zero—a story with crucial lessons for the newer generations of Cambodians and the rest of the world.

No matter how noble an idea might be, it must be pursued the right way. The end doesn’t always justify the means. No vision or plan is worth discarding our humanity.

How can we ensure that the Pol Pot atrocities never resurface anywhere in the world? We would love you to share your ideas.